u stvari, čaušesku je otplaćivao nešto i unapred, da ubrza, 88/89, mimo želje kreditora, što je pogoršalo stanje. a onda je hteo da od svoje zemlje napravi kreditora

To meet the debt repayment schedule, Ceausescu demanded a radical revision of the five-year plan that would make the early payment of foreign debt the chief priority of economic policy. No new debt was to be contracted from private lenders or other states.81 Even the contracting of loans from the Bretton Woods institutions was banned in 1988. As investment in industrial expansion was set to continue, all imports had to be cut drastically and the value of exports had to go up. While income levels were not affected negatively,82 living standards collapsed. This owed to the fact that all strategies meant to amass the dollars necessary for eliminating foreign debt by the end of the 80s were on the table, including the engineering of a massive drop in domestic supply of staples and consumer goods. Overall, between 1981 and 1989 the supply of food staples was nearly halved.83 The production of consumer goods was also nearly halved during the same period and, to make matters worse, its share in exports was increased.84 In marked contrast was similarly indebted Poland, where the government cut consumption by barely 10 percent in 1981, only to restore it to its previous levels two years later.85 Also, while in Romania non-socialist convertible currency imports fell by 43 percent between 1980 and 1983, in Poland they decreased only by 5 percent in GDP.96

To save dollars, barter deals paid for commodity imports. For example, the export of engineering industry outputs to Iran, Iraq, and socialist states was bartered for imports of oil and other commodities that otherwise would have had to be paid in scarce foreign currency. Unfortunately for the Romanian side, as a result of trade deals struck in the late 1970s, Romanian exports were sold at fixed prices that did not account for the increase in the price of energy inputs after the 1979 oil crisis. During the late 1980s, the Brasov Tractor Works (Uzina Tractorul Brasov), one of the industrial champions of Ceausescu’s Romania, was selling tractors to Iran for just under $4,000 apiece in order to pay for imported Iranian oil.87

Soon the push to pay off debt reached Stakhanovite levels: in 1988 and 1989 Ceausescu decided to pay a billion dollars of debt by selling 80 percent of the country’s gold reserves.88 As a result of these drastic measures, between 1982 and 1987 Romania boasted the fastest reduction of debt to GDP ratio in the world. Likewise, a current account deficit of $2 billion in 1982 turned into a surplus of $9 billion by 1989. In a determined show of fiscal virtue, the government budget closed with surpluses.Ironically, in terms of its external accounts and fiscal policy numbers, Romania was a top performer. In 1987, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) approached the regime’s central bank governor to convey the message that Romania’s sovereign bondholders found the early debt repayment program to be sufficiently credible. Consequently, the BIS strongly recommended that the rest of the sovereign debt should be paid at the deadlines agreed in the 1982 debt rescheduling agreement. Ceausescu vehemently rejected the recommendation and stayed the course, ending with the message that the regime was pulling the plug on Western finance for good.89 In the same year, the regime stopped communicating basic data to the Bretton Woods institutions.

The squeezing of domestic consumption through the planned reduction of demand contributed to sharp drops in GDP: from 6 percent in 1983 to –0.5 in 1985 and –5.8 percent in 1989. Indeed, the depth of austerity and the pace of the improvement in trade deficit was far in excess of what markets expected whose effects were magnified by the initiation of new and expensive infrastructure and industrial projects. As the next sections show, the result of the regime’s belt-tightening was oppositional mass mobilization.

...

To get the dollars needed to pay off foreign debt, Ceausescu decided to crack down on both private and public consumption, thus reversing two decades of progress in living standards. The provision of adequate food, housing, and health was no longer taken for granted. Schools and the extensive apartment complexes that housed the newly urbanized population saw regular electricity and heating cuts during subzero temperatures because an expanding industry struggling to meet the export targets of the regime needed more electricity. Industry earned precious hard currency, so consumers had to endure daily blackouts, even though the country produced more electricity than Spain and Italy. Spending on healthcare, the hallmark of the regime’s social progress, was also cut—so much so that by the late 1980s doctors had to offer care without the most basic supplies. Spending cuts and the effective banning of medical imports during the late 1980s led to severe shortages in medical supplies. Even essential items like insulin, cotton pads, and single-use syringes were hard to come by. Some of the weakest members of society (childless retirees, orphans, and abandoned children) were cared for in abysmal conditions. In suggestive contrast, the building of a single new coal power plant (Centrala Termoelectrica Anina) cost nearly three times more than the yearly investment in health and social assistance during the 1980s.103

The strong export orientation also meant reduced supplies of clothing, footwear, and gasoline. Eerily empty shelves, long queues for everyday items lasting hours on end, and the growth of the informal economy became the new realities of consumer life in urban areas during the 1980s. In a parallel to consumer behavior in capitalist recessions, savings deposits in 1980s Romania went up in real value per annum, even as households experienced unprecedented consumption cuts. In what seemed like an uncanny repeat of the early industrialization period of the 1950s, as the government budget was accumulating surpluses, the bout of fiscal virtue saw private consumption as a share of national income drop. And even according to government statistics, food became more expensive, with the share for this item in household budgets going up from 46 percent in 1980 to 51 percent in 1989. Moreover, as food exports increased and food rations were introduced, the per capita calorie intake fell from 3,200 to 2,900 over the same period. In this way, drastic cuts in consumption and social services undermined the very claims of socioeconomic progress that the regime’s legitimacy hinged on. 104 The belt-tightening continued even after April 1989, a date celebrated by the regime as it marked the full repayment of Romania’s foreign debt.

Austerity also made the regime increasingly derelict in keeping its promise to deliver decent working conditions. Increased work intensity, night shifts, working Sundays, and higher quotas at no extra pay became the rule in the expanding export sector as management was ordered to meet increasingly ambitious export schedules. The engine of social mobility began to sputter, as the new generations of working age peasants trained to staff the industrial infrastructure had to obtain special permits to live in the cities where they worked. Accordingly, they were forced into long commutes at a time when spending on transportation had been drastically reduced.

...

In 1987, a wildcat strike in the heavily industrialized city of Brasov demonstrated the importance of wage cuts and consumption deprivation as sources of mobilization. Crucially, scholarly accounts and memoirs of this event are in agreement that workers’ demands for restoring the pre-austerity socioeconomic status quo soon morphed into demands for regime change, storming of government buildings, and the destruction of RCP symbols.105 The strike led to a wave of arrests, prosecutions, and long prison terms for the workers involved. In the aftermath of the strike, some in the inner circle of the regime tried to temper austerity but were demoted by Ceausescu. When Florea Dumitrescu, the central bank governor and Ceausescu loyalist, suggested that the payment of the foreign debt ahead of schedule irritated foreign creditors, he was marginalized and eventually sacked.106

When the socialist social pact was challenged in Brasov, Romania’s own “magnetic mountain,” one would have expected the regime to reverse its consumption suppression strategy. This did not happen, however. Moreover, the minutes of an RCP executive committee meeting from May 5, 1989 certify that Ceausescu remained keen to divert resources away from basic consumption and towards exports.107 When trade minister Stefan Andrei asked Ceausescu to at least provide better heating in the huge housing complexes the regime had built, he learned that Ceausescu’s new strategy was to use the $2 billion accumulated in 1989 and the $5 billion in debt owed to Romania to build enough hard currency reserves to turn Romania into a creditor country.108 A former Romanian diplomat who specialized in Middle East affairs claims that in 1989 Ceausescu’s thinking went as far as planning the establishment of a development bank together with Iran.109 It became clear that once Romania was cut off from the international bond markets, Ceausescu hoped to turn Romania into a leader of newly industrializing countries, apparently with no consideration for the political costs involved.

Moreover, just as austerity was traumatizing the urban industrial working class the regime had created, the public budget was funding infrastructure and industrial investment in North and Sub-Saharan Africa, Cuba, the Middle East, and the USSR. While before 1989 this policy was presented as a calculated attempt to get the dollars needed to pay off the debt and, through barter, the commodity imports demanded by the industry, it was hard to understand why the debt payment terms of these countries extended well into the 1990s, given that Ceausescu’s plans to enter the mining business in these countries saw few concrete steps.110 It also seemed profoundly unfair that as living standards continued to drop in 1989, the regime sat on nearly $9 billion lent or invested in developing countries and the USSR.111

This extravagance in Romania’s external accounts was paid not only through extensive mass mobilization. Indeed, Brasov’s rebelling workers were the unheeded canaries in the mine to the antiregime mass mobilization that brought down the government in December 1989. Unlike negotiated transitions in Spain and elsewhere in Central Europe, the Romanian authoritarian regime died in a violent face off with a protest movement whose backbone was precisely the social class the regime had built and then betrayed: the industrial wage-earners.112 Contrary to skeptics’ assumptions, it quickly became clear that the high levels of police repression, constant surveillance, and the absence of a robust network of antigovernment activists did not prove to be insurmountable obstacles against Europe’s last popular revolutionary movement to end a particularly repressive regime and the grip of a well-entrenched “uncivil society.”

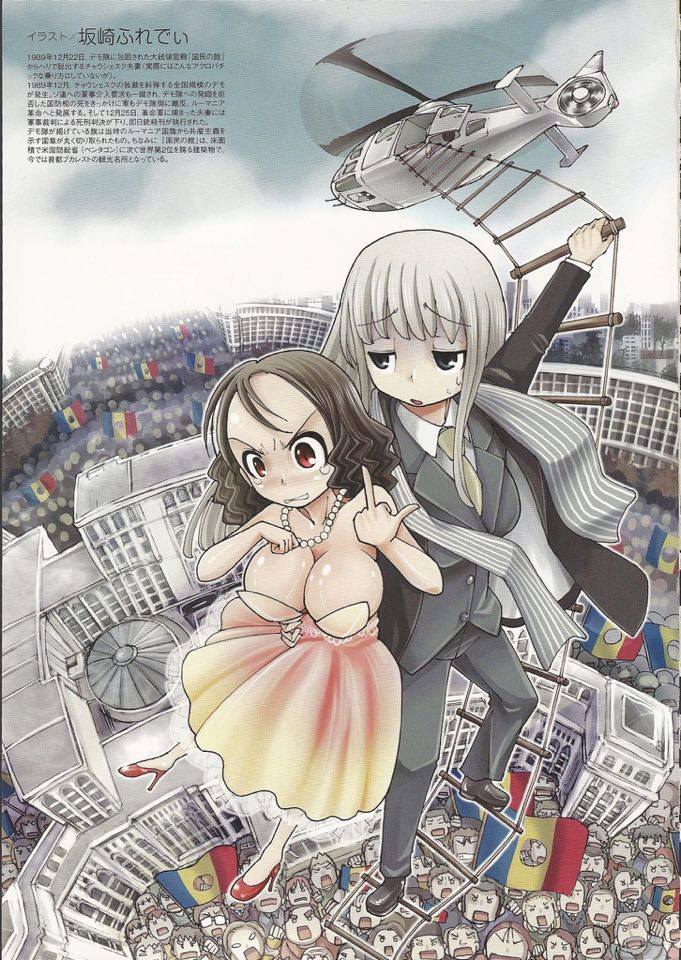

Beginning in Timisoara, a multiethnic city in the southwest, the movement spread throughout most large cities in the country. The regime’s attempts to put down the movement failed despite the deployment of the entire repressive toolbox of the police state, from the “milder” arrests, city blockades, and curfews to fire-at-will orders given to armored army regiments.113 On December 22, 1989, Ceausescu’s flight by helicopter, his abandonment by the repressive apparatus, and his execution a few days later ended Romania’s national-Stalinism. All of this, however, was not before hundreds more had died in various forms of urban warfare, the images of which were grotesquely dramatized in Western media and converted into an imagery of post-communism as a realm of violence riveted by the devastating effects of “communist” rule.135

by Indy Sun 6 Aug - 17:37

by Indy Sun 6 Aug - 17:37

паће

паће