And now, when it was once again too late for anything, his troops became ever more various, even fabulous: Great Russians, Ukrainians, Mensheviks, monarchists, murderers, martyrs, lunatics, perverts, democrats, escaped slaves from the underground chemical factories, racists, dreamers, patriots, Italians, Serbian Chetniks, turncoat Partisans who’d realized that Comrade Stalin might not reward them after all, peasants who’d naively welcomed the German troops in 1941, and now rightly feared that the returning Communists might remember this against them, dispossessed Tartars, Hiwis from Stalingrad, pickpockets from Kiev, brigands from the Caucasus who raped every woman they could catch, militant monks, groping skeletons, Polish Army men whose cousins had been murdered by the NKVD in 1940, NKVD infiltrators recording names in preparation for the postwar reckoning (they themselves would get arrested first), men from Smolensk who’d never read the Smolensk Declaration and accordingly believed that Vlasov was fighting especially for them, men who knew nothing of Vlasov except his name, and used that name as an excuse—a primal horde, in short, gathered concentrically like trembling distorted ripples around its ostensible leader, breaking outward in expanding, disintegrating circles across the map of war. When the British Thirty-sixth Infantry Brigade entered Forni Avoltri at the Austro-Italian border, they accepted the surrender of a flock of Georgian officers, no less than ten of whom were hereditary princes “in glittering uniforms,” runs the brigade’s war diary. Suddenly pistol-shots were heard. The Englishmen suspected ambush, but it turned out to be two of the princes duelling over an affair of honor. The victors’ bemusement was increased by the arrival of the commander, a beautiful, high-cheeked lady in buckskin leggings who came galloping up to berate her men for having yielded to the enemy without permission. Leaping from the saddle, she introduced herself as the daughter of the King of Georgia. (Needless to say, no kings remain in our Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, which happens to be the birthplace of Comrade Stalin.) All these worthies considered themselves to be members in good standing of Vlasov’s army. Vlasov, the Princess explained, had guaranteed the independence of Georgia . . .

НОБ за понављаче

- Posts : 37706

Join date : 2014-10-27

- Post n°101

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

vilijam t volman europa central (mislim anti-staljinisticki ali ima taj neki epski zamah)

_____

And Will's father stood up, stuffed his pipe with tobacco, rummaged his pockets for matches, brought out a battered harmonica, a penknife, a cigarette lighter that wouldn't work, and a memo pad he had always meant to write some great thoughts down on but never got around to, and lined up these weapons for a pygmy war that could be lost before it even started

- Posts : 37706

Join date : 2014-10-27

- Post n°103

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

dobra je ta knjiga. sostakovic, vlasov, staljin...

_____

And Will's father stood up, stuffed his pipe with tobacco, rummaged his pockets for matches, brought out a battered harmonica, a penknife, a cigarette lighter that wouldn't work, and a memo pad he had always meant to write some great thoughts down on but never got around to, and lined up these weapons for a pygmy war that could be lost before it even started

- Guest

- Post n°104

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

kačim ovde zbog teme, kao "eto neki novi tekst", koristi i nove dokumente iz moskovskih arhiva. nisam stručnjak za ovaj period ali mislim da ima dosta novih detalja:

Stalin, the Western Allies and Soviet Policy towards the Yugoslav Partisan Movement, 1941–4

Tommaso Piffer

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0022009417737602

[spoiler]

...

This article follows the development of Soviet policy towards the communist

partisan movement in Yugoslavia from the invasion in 1941 to the liberation of the

country at the end of 1944. In doing so, it addresses this topic for the first time

through the lens of the Soviet decision-making process, following developments

across the entire duration of the war. During 1941–2, the Comintern was indeed

concerned by Tito’s leftist stand, although this did not prevent Moscow recognizing

his role as one of the key players in the region. Over the course of the war, the

strict popular front strategy imposed on Tito in 1941 was progressively abandoned

as a response to shifts in British policy and, in 1944, Moscow gave full support to

the partisans’ take-over of the country. The Soviet attitude towards Tito was also

appreciably adapted as he changed from secretary of one of the parties subordinated

to the Comintern into the leader of a new communist state in the making.

The development of the Soviet policy, however, was not linear. On the contrary, it

took shape in the context of many uncertainties and steps back caused by a lack of

understanding of the British position, the attempt to deceive the Western Allies

about the extent of relations with Tito, and also by the emergence of different

perspectives among the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Comintern and

the Soviet military. The Soviets were largely successful in their attempt to support

Tito while avoiding repercussions for the Great Alliance, although in the long term

their achievements backfired.

- Spoiler:

...

At the end of 1941, the importance of Tito’s movement was already clear to

Dimitrov who, from September, had pushed Molotov to send military supplies to

Yugoslavia.12 The Comintern, which at that point had no connections with the

Greek communist party, was also ready to acknowledge the key role that Tito

might play in the entire region: the Albanian communist party was created in

November under Yugoslav patronage, and a dispute with the Bulgarian party

over the jurisdiction of Macedonia had already been resolved in favour of the

Yugoslavs in August 1941. Contacts with the Italian communist party were also

maintained through Yugoslavia.13 The situation was such, however, that any

public stand in the Tito-Mihailovic´ controversy was not considered advisable,

and Moscow refused to commit itself with the British.

On the one hand, the Soviets, who in September 1941 were contemplating

sending a joint mission to Mihailovic´ in collaboration with the British,14 were

unsure about what was happening in the country. At the end of November the

secretary of the Comintern, Dimitrov, asked Tito who was leading the Chetniks

and the relationship they had with the Partisans.15 When Tito replied that they

were just collaborating with the Germans, Moscow appeared unconvinced, suspecting

that it was Tito who was not doing enough to collaborate with other

antifascist forces. A few months later Dimitrov was still insisting to Tito that it

was hard to imagine that ‘London and the Yugoslav government support the

occupiers’, as he claimed, and that the issues with the Chetniks ‘must be a big

misunderstanding’.16

On the other hand, Moscow was clearly concerned that the leftist line adopted

by Tito could damage its relations with both the Yugoslav government-in-exile and

the British. Yet the possibility for the Soviets to appease the British by publicly

pushing Tito towards a conciliatory course was limited, paradoxically, by

Moscow’s claim that the European communist parties were not the ‘long arm’ of

Moscow.17 When, at the beginning of December 1941, the British incorrectly notified

them that the Chetniks had reached an agreement with the Partisans, the

Soviets could not dispute this information, as to do so would imply that

Moscow had a direct link with the Partisans or at least a link to independent

sources inside the country. Moscow simply replied that it did not consider it

advisable for the Soviet Government to intervene in Yugoslav internal affairs,18

leaving the British to deal with the mess by themselves.

At the beginning of 1942, it was difficult to see how the Soviets could square the

circle of three apparently incompatible goals: supporting Tito, avoiding the repercussions

of this policy for relations with the British when their help was more

needed than ever, and sustaining the pretence that they had no control over the

Yugoslav communist party. Tito, however, found a champion of his cause in

Moscow in Dimitrov.

Dimitrov’s first goal was to bring Tito in line with the Comintern’s official

position. On 5 March 1942 he accused Tito of giving grounds ‘for the supporters

of England and the Yugoslav government’ to suspect that the partisan movement

was ‘acquiring a communist character and [was] aiming at the Sovietisation of

Yugoslavia’. The secretary of the Comintern instructed him to ‘seriously review

[his] tactics and activities’, and reminded him that ‘the main task [was] to unite all

the anti-Hitler elements in order to defeat the occupiers’.19

Tito had good reasons to comply. The distance between him and the Soviet

leadership was, at its roots, strategic, arising out of the eternal debate inside the

international communist movement about the correct route to establish socialism.

But negotiating the turbulent politics of the 1930s in the Moscow of the Great

Purge had taught Tito the limits of his ability to manoeuvre, and especially that, to

operate freely in internal politics, he had to pay lip service to the Soviet line in the

international arena.20 He also realized that his ultra-radical line could alienate a

vast part of the population. In April, the leadership of the party increased its

campaign against ‘sectarianism’ and, under Soviet guidance, began a slow process

of ideological reorganization under the guidance of Dimitrov.21

At the same time, Dimitrov started lobbying Molotov and Stalin in favour of the

Yugoslav comrades, claiming that the British and the government-in-exile were

obstructing the anti-German effort of the resistance movement and urging the

Soviet leadership to send weapons to the Partisans.22 The Soviet government, however,

was uncertain as to how to proceed. As Andrey Vyshinskii, then Molotov’s

deputy, commented on 19 June 1942, it was difficult to keep the question of the

Partisans separated from its context, and especially from the problem of relations

with the government-in-exile. If Moscow were to address this issue, he wrote, ‘it will

be necessary to carry the matter through to the end’. ‘Truthfully’, he concluded, ‘I do

not see such a possibility’.

It took Dimitrov making an extra effort with Tito for Moscow to start considering

a new position. At the beginning of June, while Soviet representatives in

London were claiming that Moscow had no connections with Yugoslavia and

bore no responsibility for the actions of the Comintern,25 Dimitrov delivered a

lesson in popular-front tactics to Tito. The Partisans, he explained, were right to

expose the activities of the Chetniks, but this should not be presented as an attack

on the Yugoslav government, but rather as an appeal to it, ‘emphasizing that the

fighting Yugoslav patriots are entitled to expect that government’s support’. Part of

the Chetniks, he argued, should be won over, others neutralized and only ‘the most

malicious part of them’ destroyed ‘without mercy’. He believed that the campaign

against the class enemy should be conducted in the name of unity, without giving

the impression that it was party oriented. He therefore considered it expedient to

organize some form of appeal ‘by well-known Yugoslav public figures and politicians

against collaborators and in favour of the Part[isan] people’s liberation

army’, and possibly also to set up a ‘national committee for aid for the

Yugoslav people’s war of liberation’ with the participation of ‘well-known patriotic

Serb, Croat, Montenegrin, and Slovene public figures’.26 Tito took notice. On 16

June, he summoned a ‘Congress of Patriots from Montenegro, the Bay of Kotor

and Sandzˇak’ which issued a declaration that did not refer to the communist

organization, but praised the three big powers and made an appeal to the

Yugoslav government-in-exile instead of attacking it.27 A few days later, on 19

June, he made a speech that all but abandoned the leftist tone of his previous

statements and condemned the ‘sectarianism’ of the party.28

Beginning in August 1942, the new Soviet course towards Yugoslavia developed

in three directions. Firstly, on 3 August, a carefully worded memorandum that

accused the Chetniks of fighting the Partisans in collaboration with the occupiers

was presented to the ambassador of the Yugoslav government-in-exile in

London.31

Secondly, Moscow kept diplomatic contacts with the Yugoslav government on a

different track and, at the end of August, it expressed a desire to elevate relations to

the level of establishing an embassy. Tito protested vehemently.32 At the end of

November, much to the surprise of the Yugoslavs, Moscow also offered to send a

military mission to establish direct contact with Mihailovic´ .33

Thirdly, Dimitrov maintained a watchful eye over Tito to ensure that he stayed

on track. A few days after the memorandum against Mihailovic´ was handed to the

Yugoslavs, Dimitrov instructed Tito not to call his brigades ‘proletarian’ but rather

‘shock brigades’ and urged him to understand that this had ‘enormous political

significance, both for consolidating people’s forces against the occupiers and collaborators

within the country and for foreign countries’. Dimitrov also reminded

him that he was waging a people’s liberation war and not a ‘proletarian struggle’,

and that he should ‘quit playing right into the hands of the enemies of the people,

who will always make vicious use of any such lapses on your part’.34 The haggling

continued for the rest of 1942. When, in November, Tito informed Moscow that he

intended to form ‘something like a government’, Dimitrov urged him not to give to

this organization a partisan character, asking for the abolition of the monarchy

or attacking the Government-in-exile with which the Soviet Union had treaty

relations.35 Again, Tito complied. When, at the end of November, he created the

Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), he gave

to it a very broad programme, with which almost everybody could identify.

...

The Foreign Office was

also worried about the repercussions of its policy for Moscow. But the immediate

support given to the Chetnik movement by the Yugoslav government limited the

options at British disposal, and the Foreign Office rallied behind it to defend

Mihailovic´ . As a consequence, when the Yugoslavs presented a counter memorandum

rebuffing the Soviet accusations, Moscow was unable to take the affair further

without creating a breach with the British. Moreover, it could not substantiate its

allegations and challenge the Yugoslav counter memorandum without using the

information provided by Tito and thus revealing its contact with the Partisans.

...

In the following months, while Soviet relations with Tito were punctuated by

occasional disagreements and complicated by Tito’s frustration with the lack of

Soviet military support,38 Moscow seemed to be unsure as to whether it was

better openly to support the Partisans, work for an agreement with the Chetniks,

or simply remain steadfast in their policy of denial. On 5 March 1943, for example,

the British government asked Moscow for support in getting in touch with the

Partisans.39 Molotov’s first reaction was, as usual, to deny the existence of any

connections with Yugoslavia,40 but then he pondered over whether it might be expedient

to present a more articulate reply. The several different drafts of his response,

which were prepared, are indicative of the doubts that were harboured in Moscow.

...

Moscow’s paralysis lifted at the end of 1943, in the context of the transition in

Soviet policy towards the entire communist movement. In May, Moscow had

announced the disbandment of the Comintern. Although this move is generally

interpreted as an attempt to improve relations with the Western Allies, privately

Stalin explained that it was also designed to enlarge the field of manoeuvre of the

communist parties which, due to their participation in the Comintern, were ‘falsely

accused of supposedly being agents of a foreign state’.43 In June it was decided to

create a Department of International Information, a sort of umbrella organization

secretly headed by Dimitrov which was in charge of ‘special institutes’ that inherited

the functions of the Comintern.44 What happened later, however, was a much

greater change. Although the institutes were created immediately, the Department

that was supposed to control them was not, and its functions were approved only in

September 1944. In the meantime, the institutes apparently operated without much

direction from the centre, and were severally handicapped by organizational problems

and by the fact that most foreign cadres were going back to their own countries.

Dimitrov, who in any case had to take frequent periods of leave due to illness,

was progressively side-lined, while Stalin and Molotov personally directed the

communist parties either through personal meetings with their leaders or through

the missions dispatched by Soviet military intelligence.

...

In the meantime, in Yugoslavia the pace of events began to accelerate. Tito had

good reason to think that, in the Western field, the wind was changing in his

favour. The British, he cabled to Dimitrov, were offering help ‘now that we have

almost liquidated Mihailovic´ and his Chetniks’ and it was necessary to accept their

offer of material aid ‘and win them over politically’.45 Tito’s impression that the

standing of the Partisans was improving was confirmed when one of the British

agents told him that in Cairo there were two factions, one pro-Mihailovic´ and one

pro-Tito, but that the military circles were unhappy with British support for the

former. Tito quickly passed this information to Dimitrov, adding that the British

‘want to know too much about our army’ but that he was giving them only ‘the

information that we think can be given’.46 During the same period, Tito pushed

neighbouring parties to take a more aggressive stand against their internal enemies.

In August, he forced the Albanian communist party to denounce an agreement

with the nationalists of the Balli Kombe¨ tar, thus escalating the confrontation with

non-communist groups. At the same time, he extracted from the Greek communist

party the right to organize a Slav National Liberation Front in Greek Macedonia,

which soon manifested separatist tendencies. In September, he sharply criticised the

Greek comrades for allowing their national liberation movement to fall under

British influence.47 Finally, on 2 October, Tito informed Dimitrov that he did

not recognise the authority of the government-in-exile or the King, that he did

not intend to allow their return to the country, and that the AVNOJ should be

considered the only legal authority in the country. Significantly he reported that he

had communicated his intentions to Fitzroy Maclean, Churchill’s personal envoy

to the Partisans, and that Maclean had let the Partisans know that the British

government would not strongly uphold the king and the government-in-exile.48

Although the telegram was widely circulated among the Soviet leadership, which

had strongly discouraged Tito to take the same step a year earlier, this time

Moscow did not react. Excluding the argument that the implications of this

news had not been fully understood, it can be argued that Moscow preferred to

remain on the fringe of the action, keeping a free hand to stop Tito if his gamble

backfired or to support him in case of success. Which, in the end, is exactly what

happened.

...

At the beginning of 1944, the Soviets continued to claim that they did not have

enough information about the situation in Yugoslavia to take any action, and

under this pretext they refused to issue a declaration advocating an agreement

between Tito and the king.64 Behind the scenes, they were overturning one of the

key features of the popular front strategy established in 1941, suggesting to Tito

that he reject any agreement with the Yugoslav government-in-exile. It was

Churchill who took the initiative, asking Tito, on 5 February, if the dismissal of

Mihailovic´ could open up the possibility of an agreement between the Partisans

and the king. Tito forwarded the letter to Dimitrov, pointing out that although he

had plenty of reasons to refuse the deal, the matter was serious enough to ask the

opinion of Stalin himself.65 Tito, who was used to being reprimanded by Moscow

over his direct confrontations with the Government-in-exile, this time received a

different response. Though Dimitrov, Stalin and Molotov let him know that he

should reply to ‘the Englishman’ that he too favoured the unity of the Yugoslavs

and that, for this reason, the government-in-exile, including Mihailovic´ , should be

eliminated, the AVNOJ recognized as the sole government of Yugoslavia and the

king submitted to its law. If the king was willing to accept these conditions, they

stated, the AVNOJ would not object to cooperating with him, but of course the

ultimate fate of the monarchy would only be decided after the end of the war Tito

was also instructed to refer to Stalin in the subsequent telegrams as to ‘the friend’.66

Tito wrote his reply to Churchill on 9 February, using the wording of the text he

had received from the Kremlin.

...

Completing the process of side-lining Dimitrov, which had started with the

disbandment of the Comintern, Tito was informed that from April he could communicate

directly with Molotov, and that Dimitrov would have nothing more to do

with Yugoslavia. Soviet correspondence with Tito shows that starting from 1944,

the Soviet leadership was not only concerned to reassure the Western Allies, but

also to reassure Tito, who was clearly emerging as the master of postwar

Yugoslavia. In the same letter, which confirmed the marginalization of Dimitrov,

Stalin and Molotov personally assured Tito that they considered Yugoslavia an

ally of the Soviet Union, and Bulgaria an enemy, and that even if the situation

changed in Bulgaria they wanted Yugoslavia to be their ‘principal support in

South-eastern Europe’. The two leaders added that they had no plans for the

‘sovietisation’ of either Yugoslavia or Bulgaria, which they characterised as democratic

countries allied with the Soviet Union, and that whatever Dimitrov was

thinking, any decision on the question of Macedonia would be taken with Tito’s

agreement73. From April 1944 onwards, the tone of Soviet correspondence with

Tito changed significantly. While Dimitrov had addressed Tito as a subordinate,

Molotov generally expressed himself in terms of giving advice rather than directives.

In June, Korneev was also reminded that he should make suggestions to Tito

only when he was asked to do so, and that he should not overwhelm him with

questions ‘especially when he shows no desire to express an opinion’.74

...

While doing their best to help the Partisans, Molotov and Stalin remained determined

that Tito’s increasing hold over the country did not appear to be orchestrated

by Moscow. KGB officers attached to the mission were instructed to keep a

low profile demonstrate ‘extreme caution and tact so as not to provoke complains

that we are interfering in the internal affairs of Yugoslavia or that we are not loyal

to the allies’.81 The same caution encouraged Moscow to reject the option to sever

relations with the Yugoslav government-in-exile, which had been contemplated

in the first months of the year. In April, meeting Djilas in Moscow, Molotov

guaranteed that the Soviet government intended to recognize the AVNOJ as

the legitimate government of Yugoslavia, but he also made it clear that this step

was premature and that it should be done with consideration for relations with

the Western Allies and the situation in other countries. Although Djilas

was pushing for a quick solution, both he and Molotov agreed that international

recognition depended on the capacity of Tito to strengthen his position in Serbia.

...

The Western Allies remained a continuous source of concern. Tito and the

Soviets became increasingly suspicious that, notwithstanding Churchill’s public

statements, the British were still surreptitiously supporting Mihailovic´ in the

hope of turning his forces against the Partisans.85 By the beginning of June, Stalin

was also convinced that the British were plotting to kill Tito.When he barely survived

a surprise attack by the Germans and was evacuated to Bari, Stalin summoned Djilas

and asked himto warn Tito to be ‘wary of our ‘‘foreign friends’’’ and keep the details

of his return trip strictly secret. ‘Do not forget that there are cases where planes break

down in the air’, he said, in an apparent reference to the rumours that the death in a

flying accident of the Polish general Sikorski had been orchestrated by London.86

...

The agreement between Tito and Subasic´ was signed on 16 June.

The AVNOJ was recognized as the only legitimate government in Yugoslavia and

Subasic´ agreed to form his new administration without those elements compromised

by the German occupation. The question of the monarchy was postponed

until the end of the war.

The signing of the pact did not ease Moscow’s concern. The KGB, which intercepted

a report by Churchill on this matter, informed Stalin that neither the Prime

Minister nor the British Foreign Office was fully satisfied, and that the conservative

circles in the British Foreign Office were working against Tito, claiming that he did

not have enough support in Serbia. In his report to Stalin, Korneev sounded a

similarly alarmed note, claiming that British support to the Partisans was more

fictitious than real, that the British had not really broken off relations with

Mihailovic´ and that they were secretly mobilizing all their reactionary forces to

oppose the Partisan army in the event of a German withdrawal.91 The British, who

had cultivated the illusion of having tied Tito to an agreement for the restoration of

the monarchy, were indeed disappointed, sensing that they were just giving Tito

what he wanted without any reasonable concessions on his side.92 But as Eden had

commented at the beginning of June, the British only had themselves to blame for

this situation, as ‘the Russians have merely sat back and watched us doing their

work for them’.93 At the same time, the Foreign Office vetoed an SOE plan to reestablish

connections with Mihailovic´ out of fear of losing Tito’s confidence, and

for the same reasons the British also forced the USA to withdraw the intelligence

mission they still maintained with the Chetniks.94

...

The Yugoslav case suggests that, in the context of the shifting balance of forces

among the Western Allies, Moscow was ready to put aside the popular front strategy

and to encourage local communists to challenge the political order supported

by the British and the Americans while the Second World War was still raging.

The modification of Soviet policy in 1944 also has the potential to shed light on the

earlier period, highlighting that the disagreement with the Yugoslavs over

the nature of the war in 1941–3 never really brought into question the Soviets’

recognition of the preeminent role played by Tito among the neighbour parties.

The example of Yugoslavia, however, also shows that this apparently clear strategy

covered deep uncertainties on the Soviet side as to the real intentions of the British,

the real space of manoeuvre enjoyed by Moscow and the way in which relations

with a new communist state in the making should be established. It also shows that,

trapped in the Marxist world-view which postulated the incompatibility of

the socialist and capitalist worlds, Moscow was often unable to understand its

opponents, looking for conspiracies where they did not exist.

In the short term, Soviet policy appeared successful. By directing Tito to abandon

his radical stance and adopt the slogan of national liberation, Moscow helped

him to gain the confidence of the British, establishing the impression that a collaboration

between the Partisans and the King was indeed possible. Then the Soviets

were able to support the communist take-over of the country without it affecting

their relations with the Western Allies. Tito’s flight to Moscow was a brutal

awakening for Churchill, who only then realized that in Tito the British had

‘nursed a viper’.100 The Soviets were also able convincingly to deny until the end

the extent of their involvement with the Yugoslav communist movement, thus

avoiding the risk that, if anything went wrong, the situation could be ascribed to

them. In all this, they provided at the crucial moment the military, financial and

diplomatic support that the Partisans needed to defeat their internal enemies and to

gain credibility in the international area. Tito played his cards well, paying lip

service to the Soviets when needed and continuing to advance his cause step by

step while maintaining their support.

The seeds for further conflicts, however, had been planted. Paradoxically, by

pushing Tito to widen his popular base in Yugoslavia after 1942, the Soviets had

established him as the leader of a communist state that was now challenging

Moscow’s supremacy. Created by Stalin and nursed by Churchill, ‘the viper’

Tito was now ready to bite eastward. Exacerbated by Tito’s attempt to impose

his leadership on the other ‘popular democracies’ in the Balkans after the war, the

conflict between the two leaders of the communist movements eventually became

unmanageable, and in 1948 led to the most serious split in the communist world.

http://sci-hub.bz/http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0022009417737602

- Guest

- Post n°105

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

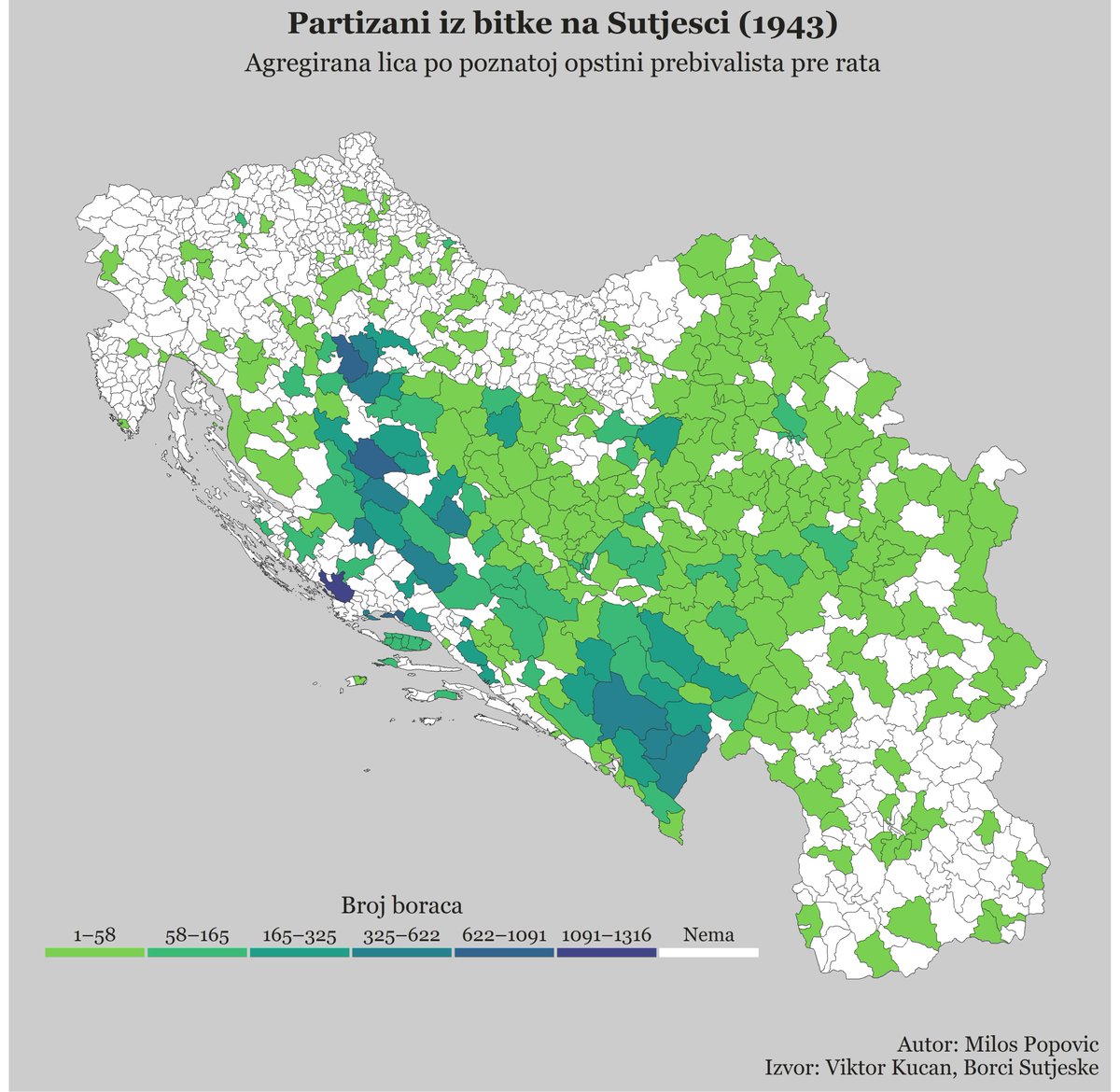

Milos Popovic @milos_agathon пре 34 минута

In 1943, #Yugoslav #communists took heavy losses in Battle of Sutjeska & #Tito barely survived #axis offensive

My new #map shows #partisan fighters who took part in battle by place of birth

#war #combat #WW2 #violence #conflict

#rstats #ggplot2 #cartography #data #dataviz

- Posts : 11765

Join date : 2014-10-27

Location : kraljevski vinogradi

- Post n°106

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Ističu se Dinaridi. Blut und Boden.

_____

Ha rendelkezésre áll a szükséges pénz, a vége általában jó.

- Posts : 10694

Join date : 2016-06-25

- Post n°107

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Vidi ti to, a kekeci nam traze neke slike i filmove(Bitka na Neretvi), a vidi mapu iznad.

Isticu se Kordun, Dinara, Istocna Hercegovina i Djurisicevi cetnici iz CG...

Isticu se Kordun, Dinara, Istocna Hercegovina i Djurisicevi cetnici iz CG...

- Posts : 8696

Join date : 2016-10-04

- Post n°110

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Одлична мапа.

Види се да је НОП био не само распрострањен по целој земљи, него и да су успевали да пошаљу људе тамо где су потребни.

Види се да је НОП био не само распрострањен по целој земљи, него и да су успевали да пошаљу људе тамо где су потребни.

- Posts : 6599

Join date : 2014-12-09

- Post n°111

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Sotir wrote:по целој земљи

Ако је цела земља Србија, РС и РСК.

_____

"Mogu li ja da kažem ili ćete Vi da vodite intervju sami sa sobom? Samo kad bih mogla da kažem nešto… Prvo, uvek smo govorili našim građanima da ne možemo i nećemo da gledamo na EU kao na ćup sa novcem. Da bolji kvalitet života, radna mesta i bolje plate moraju doći od nas samih i snage naše ekonomije. Želimo da budemo deo EU jer je to mirovni projekat i jer delimo vrednosti sa EU." - Ana Brnabić

- Guest

- Post n°112

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

vidimo kako se neke zemlje danas odnose prema nasledju nob, iako bi po ovoj mapi pomislili drugacije

ovde ce to svakako primitivna srbocetnicka nedicevstina da unisti ili prepusti propadanju

Ljubljana potražuje i umetnine koje se čuvaju u Domu Vojske Srbije, nekadašnjem Maršalatu, Predsedništvu, Muzeju vazduhoplovstva, rezidenciji u Užičkoj 7... Na listi su mahom ulja na platnu, akvareli i grafiti, ali i vajarske figure, od bronze i slonovače. Uz to, Slovenci zahtevaju i desetine istorijskih predmeta koji se čuvaju u Srbiji.

Među njima su zastave slovenačkih jedinica iz NOB-a, radio stanica iz vremena italijanske okupacije, partizanski top i sanitetski materijal iz zbirke Vojnog muzeja na Kalemegdanu.

ovde ce to svakako primitivna srbocetnicka nedicevstina da unisti ili prepusti propadanju

- Posts : 10694

Join date : 2016-06-25

- Post n°113

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

uskok i ajduk wrote:Sotir wrote:по целој земљи

Ако је цела земља Србија, РС и РСК.

Zavuce ga uskok hajducki.

Kakva crna celja zemlja, slovenija i veci deo hrvatske nisu imali borca, makedonija isto...

- Posts : 15575

Join date : 2016-03-28

- Post n°114

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

kako te nije blamZuper wrote:uskok i ajduk wrote:

Ако је цела земља Србија, РС и РСК.

Zavuce ga uskok hajducki.

Kakva crna celja zemlja, slovenija i veci deo hrvatske nisu imali borca, makedonija isto...

Borbe u Sloveniji 1942.

Izaberi pojam

Za ovaj pojam je pronađeno 262 hronoloških zapisa, 605 dokumenata i 45 fotografija.

[color:aee0=rgba(69, 54, 37, 0.6)]http://znaci.net/damjan/pojam.php?br=1223

_____

Što se ostaloga tiče, smatram da Zapad treba razoriti

Jedini proleter Burundija

Pristalica krvne osvete

- Posts : 10694

Join date : 2016-06-25

- Post n°116

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Bitke u Alpima i napad na Vuciju jazbinu...

A ima i video snimak: film "Bitka na Neretvi"...

A ima i video snimak: film "Bitka na Neretvi"...

- Posts : 15575

Join date : 2016-03-28

- Post n°117

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Lololo jel dotle ide ta ideolska ostrascenost, do decijeg negiranja i durenja ?

_____

Što se ostaloga tiče, smatram da Zapad treba razoriti

Jedini proleter Burundija

Pristalica krvne osvete

- Posts : 15575

Join date : 2016-03-28

- Post n°118

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Msm vikipedija ima pregledan deo o nob po republikama, tako da lako vide aktivnosti i u makedoniji i u sloveniji , pa me znaima jel upitanju cisto negiranje toga bez pokrica il imas nesto da napises/okacis na tu temu

_____

Što se ostaloga tiče, smatram da Zapad treba razoriti

Jedini proleter Burundija

Pristalica krvne osvete

- Posts : 22555

Join date : 2014-12-01

- Post n°119

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Nema potrebe da se raspravljate o stvarima koje mapa ne pokazuje. Trik je da je to mapa sa borcima koji su učestvovali u bici na Sutjesci.

Za one sa jeftinijim ulaznicama, to su najbolje jedinice partizanske vojske, prateće jedinice glavnog štaba, proleterske brigade, dakle jezgro NOP-a/NOVJ-a. Zato sam i okačio gore "Poznaje se ko je komunista". Te trupe su bile ideološki na najispravnijoj mogućoj liniji, tvrdo jezgro, uvek uz Tita, bespogovorni izvršioci svakog naređenja. Stoga je gornja mapa jedan fin prikaz odakle su dolazili tvrdokorni komunisti koji su bili uz Tita i partiju i koji su na sebe prihvatali najteže borbe.

Naravno da je bilo i drugih brigada, jedinica, borbi, nije ta mapa prikaz teritorija na kojima su vođene bitke, nego bukvalno spisak teritorija koje su dale najbolje i najtvrdokornije borce partizanskom pokretu. Po borbenoj efikasnosti i ubojitosti su mogle da im pariraju samo još krajiške brigade, kojima je pak bila prednost što su protiv ustaša imale +10 na attack power, +20% attack speed, +15% frenzy kao i 4x critical damage na svaki open wounds ustaša.

Po borbenoj efikasnosti i ubojitosti su mogle da im pariraju samo još krajiške brigade, kojima je pak bila prednost što su protiv ustaša imale +10 na attack power, +20% attack speed, +15% frenzy kao i 4x critical damage na svaki open wounds ustaša.

Mape se moraju tumačiti. I naravno, Srbi su bili najbolji komunisti

Za one sa jeftinijim ulaznicama, to su najbolje jedinice partizanske vojske, prateće jedinice glavnog štaba, proleterske brigade, dakle jezgro NOP-a/NOVJ-a. Zato sam i okačio gore "Poznaje se ko je komunista". Te trupe su bile ideološki na najispravnijoj mogućoj liniji, tvrdo jezgro, uvek uz Tita, bespogovorni izvršioci svakog naređenja. Stoga je gornja mapa jedan fin prikaz odakle su dolazili tvrdokorni komunisti koji su bili uz Tita i partiju i koji su na sebe prihvatali najteže borbe.

Naravno da je bilo i drugih brigada, jedinica, borbi, nije ta mapa prikaz teritorija na kojima su vođene bitke, nego bukvalno spisak teritorija koje su dale najbolje i najtvrdokornije borce partizanskom pokretu.

Po borbenoj efikasnosti i ubojitosti su mogle da im pariraju samo još krajiške brigade, kojima je pak bila prednost što su protiv ustaša imale +10 na attack power, +20% attack speed, +15% frenzy kao i 4x critical damage na svaki open wounds ustaša.

Po borbenoj efikasnosti i ubojitosti su mogle da im pariraju samo još krajiške brigade, kojima je pak bila prednost što su protiv ustaša imale +10 na attack power, +20% attack speed, +15% frenzy kao i 4x critical damage na svaki open wounds ustaša.Mape se moraju tumačiti. I naravno, Srbi su bili najbolji komunisti

- Posts : 10694

Join date : 2016-06-25

- Post n°121

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Filipenko wrote:Nema potrebe da se raspravljate o stvarima koje mapa ne pokazuje. Trik je da je to mapa sa borcima koji su učestvovali u bici na Sutjesci.

Za one sa jeftinijim ulaznicama, to su najbolje jedinice partizanske vojske, prateće jedinice glavnog štaba, proleterske brigade, dakle jezgro NOP-a/NOVJ-a. Zato sam i okačio gore "Poznaje se ko je komunista". Te trupe su bile ideološki na najispravnijoj mogućoj liniji, tvrdo jezgro, uvek uz Tita, bespogovorni izvršioci svakog naređenja. Stoga je gornja mapa jedan fin prikaz odakle su dolazili tvrdokorni komunisti koji su bili uz Tita i partiju i koji su na sebe prihvatali najteže borbe.

Naravno da je bilo i drugih brigada, jedinica, borbi, nije ta mapa prikaz teritorija na kojima su vođene bitke, nego bukvalno spisak teritorija koje su dale najbolje i najtvrdokornije borce partizanskom pokretu.Po borbenoj efikasnosti i ubojitosti su mogle da im pariraju samo još krajiške brigade, kojima je pak bila prednost što su protiv ustaša imale +10 na attack power, +20% attack speed, +15% frenzy kao i 4x critical damage na svaki open wounds ustaša.

Mape se moraju tumačiti. I naravno, Srbi su bili najbolji komunisti

Te trupe su bila najblize teritoriji koju su nemci najteze kontorlisali iz geografskih razloga pa su tamo utekli da se sakriju.

To nije samo slucaj sa partizanima nego i sa Srbima kada su bezali pred Turcima u svoje vreme. Nije cudno zasto je to bila bas Sutjeska.

Visoke planine sa prasumom...

Tu se nalazi najvis vrh BiH, Maglic skoro 2 500 m nadmorske visine.

Imam prijatelja koji je posle rata '90ih sluzio u Foci i okolini i kaze kada padne noc na mrtvoj strazi u tim brdima i sumama smrzne se coveku govno zbog ukupne atmosfere...

Sam kraj je mozda poznatiji po cetnicima nego li partizanima...

Da se ne zajebajemo...

Koliko znam plan odbrane Kraljevine Jugoslavije je podrazumevao odbranu upravo tog kraja kao osnove koja moze nekako preziveti zbog terena. Od Pala preko Istocne Hercegovine i zapadne CG(Stara Hercegovina) do Boke. Zato je kralji cela svita iz Niksica otisla prema Grckoj jer je odbrana zapadnih delova te teritorije potpuno pukla u Aprilskom ratu, sto nije bilo planirano.

- Posts : 22555

Join date : 2014-12-01

- Post n°122

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Ne, te trupe nisu bile najbliže toj teritoriji. Te trupe su se našle tamo jer su početkom godine ustaše, četnici i Nemci udarili na bihaćku republiku, pa se deo trupa pod komandom glavnog štaba odvojio od glavnine i otišao prema Neretvi pošto su saznali da je cilj operacije uništenje vrhovnog štaba, sa ciljem da odvuku pritisak sa većine partizanske vojske. To su i uspeli, ali se potera ustaša, četnika i Nemaca nastavila, pa su partizani morali da se probijaju kroz Italijane do Neretve, pa onda preko Neretve kroz nove četničke formacije. Zatim je bio kratak predah dok su razmenjeni zarobljenici iz bitke na Neretvi i dok su Nemci dovukli trupe sa istočnog fronta za uništenje partizana i onda kroz dva meseca iznova, kada dolazi Sutjeska.

Dakle, te trupe su bile najbolje čime su partizani raspolagali, ali šestomesečne borbe su uzele danak, imale su velike gubitke, što od neprijatelja i domaćih izdajnika, što od bolesti, što od gladi. Pravo je čudo da su uopšte opstali. No, kao što rekoh, to što su se našli na tom prostoru nije nikakva slučajnost - tamo su ih poterali, ne zato što su "bile blizu pa su išli tamo da se sakriju", jer je glavnina partizanske vojske bila početkom 1943. na prostoru bihaćke republike, odnosno u zapadnoj Bosni, gde su se borili koliko su mogli. Te priče o bežanju u šumu možete da pričate nekom drugom, ko pojma nema o tokovima događaja.

Uzgred, te iste trupe su prilikom oslobađanja Bihaća, ako me sećanje ne vara, zarobile oko 1000 ustaša i 600 četnika koji su ga bratski branili, i potom ih postreljali. Sad, da li beše 1000+600 ili 1600+1000, mislim da se ova druga brojka odnosu na opsednutu Foču kada su Nemci došli da deblokiraju grad u kome je bilo 1600 Italijana i 1000 četnika u bratskoj odbrani i tom operacijom je otpočela bitka na Sutjesci, ali jbg, stari se...

Sad, da li beše 1000+600 ili 1600+1000, mislim da se ova druga brojka odnosu na opsednutu Foču kada su Nemci došli da deblokiraju grad u kome je bilo 1600 Italijana i 1000 četnika u bratskoj odbrani i tom operacijom je otpočela bitka na Sutjesci, ali jbg, stari se...

Dakle, te trupe su bile najbolje čime su partizani raspolagali, ali šestomesečne borbe su uzele danak, imale su velike gubitke, što od neprijatelja i domaćih izdajnika, što od bolesti, što od gladi. Pravo je čudo da su uopšte opstali. No, kao što rekoh, to što su se našli na tom prostoru nije nikakva slučajnost - tamo su ih poterali, ne zato što su "bile blizu pa su išli tamo da se sakriju", jer je glavnina partizanske vojske bila početkom 1943. na prostoru bihaćke republike, odnosno u zapadnoj Bosni, gde su se borili koliko su mogli. Te priče o bežanju u šumu možete da pričate nekom drugom, ko pojma nema o tokovima događaja.

Uzgred, te iste trupe su prilikom oslobađanja Bihaća, ako me sećanje ne vara, zarobile oko 1000 ustaša i 600 četnika koji su ga bratski branili, i potom ih postreljali.

Sad, da li beše 1000+600 ili 1600+1000, mislim da se ova druga brojka odnosu na opsednutu Foču kada su Nemci došli da deblokiraju grad u kome je bilo 1600 Italijana i 1000 četnika u bratskoj odbrani i tom operacijom je otpočela bitka na Sutjesci, ali jbg, stari se...

Sad, da li beše 1000+600 ili 1600+1000, mislim da se ova druga brojka odnosu na opsednutu Foču kada su Nemci došli da deblokiraju grad u kome je bilo 1600 Italijana i 1000 četnika u bratskoj odbrani i tom operacijom je otpočela bitka na Sutjesci, ali jbg, stari se...

- Posts : 35861

Join date : 2012-02-10

- Post n°123

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Tu u pratecem bataljonu je bio i moj pradeda (mislim da je u to vreme bio zaduzen za arhivu, pa ako sta fali, a fali, eto izvin'te). Rado bi ostao u Macvi da se moglo.

_____

★

Uprava napolje!

- Posts : 82799

Join date : 2012-06-10

- Post n°124

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Zuper wrote:uskok i ajduk wrote:

Ако је цела земља Србија, РС и РСК.

Zavuce ga uskok hajducki.

Kakva crna celja zemlja, slovenija i veci deo hrvatske nisu imali borca, makedonija isto...

Bedo ljudska.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/hab3045/4202321073

_____

"Oni kroz mene gledaju u vas! Oni kroz njega gledaju u vas! Oni kroz vas gledaju u mene... i u sve nas."

Dragoslav Bokan, Novi putevi oftalmologije

- Guest

- Post n°125

Re: НОБ за понављаче

Re: НОБ за понављаче

u sloveniji je bilo manje saradnika okupatora nego u srbiji zvalavih cetnika, nedicevaca i ljoticevaca

boomer crook

boomer crook by boomer crook Fri Jul 14, 2017 10:39 am

by boomer crook Fri Jul 14, 2017 10:39 am