MNE wrote:malo mu je zajebano što je trenutno promjena vlasti u USA pod optužnicom

Malo mu je zajebanije to što uopšte mora da se uzda u nešto poput promjene

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuMNE wrote:malo mu je zajebano što je trenutno promjena vlasti u USA pod optužnicom

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuVilmos Tehenészfiú wrote:Ma jok, ovo i ono sto je bilo pre neki dan kada je zvao ove influensere sa telegrama je bilo da osokoli raju, nema predaje, dobro nam ide, jebemo im kevu sve u 16 a busimo im te famozne leopard tenkove kao sir. Jasno je da on ovako ide jako do samog kraja, ali nema jake - osim ako se Ukrajine ne resi da grupise mnogo vojske na jednom mestu pa on padne u iskusenje da im jednim potezom zbrise pola vojne efektive. No Ukrajinci nisu sisali vesla, pa to nece da urade.fikret selimbašić wrote:

Ovo:

I ne mislim da je lud i bolestan. Mene sve viđeno mnogo podsjeća na sastanke i obraćanja u par predinvazionih dana, with a vengeance.

U stvari njegova taktika je da tera ovako dok se ne promeni vlast u Americi. A ako se ipak ne promeni, e onda jebigica. Nema on strategiju, on je politicar ranga Milosevica; moze danas da te zajebe, ali ne racuna sta moze zbog tog zajeba da bude prekosutra.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuVilmos Tehenészfiú wrote:

Ma jok, ovo i ono sto je bilo pre neki dan kada je zvao ove influensere sa telegrama je bilo da osokoli raju, nema predaje, dobro nam ide, jebemo im kevu sve u 16 a busimo im te famozne leopard tenkove kao sir. Jasno je da on ovako ide jako do samog kraja, ali nema jake - osim ako se Ukrajine ne resi da grupise mnogo vojske na jednom mestu pa on padne u iskusenje da im jednim potezom zbrise pola vojne efektive. No Ukrajinci nisu sisali vesla, pa to nece da urade.

Vilmos Tehenészfiú wrote:

U stvari njegova taktika je da tera ovako dok se ne promeni vlast u Americi. A ako se ipak ne promeni, e onda jebigica. Nema on strategiju, on je politicar ranga Milosevica; moze danas da te zajebe, ali ne racuna sta moze zbog tog zajeba da bude prekosutra.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuPrvi pasus: ne, jer je potreban izgovor. Vojska koja seci u šumi nije dovoljna opasnost. Masa oklopa koja se valja iza brda je već bolji izgovor. Kritična masa skoncentrisana na malom prostoru koja napreduje ka frontu je još bolji izgovor.Filipenko wrote:Vilmos Tehenészfiú wrote:

Ma jok, ovo i ono sto je bilo pre neki dan kada je zvao ove influensere sa telegrama je bilo da osokoli raju, nema predaje, dobro nam ide, jebemo im kevu sve u 16 a busimo im te famozne leopard tenkove kao sir. Jasno je da on ovako ide jako do samog kraja, ali nema jake - osim ako se Ukrajine ne resi da grupise mnogo vojske na jednom mestu pa on padne u iskusenje da im jednim potezom zbrise pola vojne efektive. No Ukrajinci nisu sisali vesla, pa to nece da urade.

Svašta. Pa evo pre mesec dana se znalo da je u sumama istočno od Zaporozja koncentrisano 10-ak brigada za ofanzivu sa nato opremom. I te kako su imali priliku. Ali eto, Putin je bolji covek od mene, ja bih tu bacio bar 2-3 takticke, dok on stedi ukrajinske civile i infrastrukturu, makar 50k Rusa izginulo i Krim bio odsecen.Vilmos Tehenészfiú wrote:

U stvari njegova taktika je da tera ovako dok se ne promeni vlast u Americi. A ako se ipak ne promeni, e onda jebigica. Nema on strategiju, on je politicar ranga Milosevica; moze danas da te zajebe, ali ne racuna sta moze zbog tog zajeba da bude prekosutra.

I nova vlast ce, kao sto si i sam primetio, biti po obicaju jos gora od stare.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuAlexei Yurchak: The present moral catastrophe, the USSR, and Putin | Postsocialism

This post is a shortened translation of an interview A. Yurchak gave in April 2023 to Radio Svoboda.* Any mistakes of translation are my own.

The original is here. I mainly cut the interviewer’s text

Interviewer: I was sure that the Soviet Union would stand for another thousand years, but I was not at all surprised when it disappeared. I kept thinking that during the years of Brezhnev’s stagnation, disbelief was universal, and people pretended to be serving a number at meetings, rallies and demonstrations. In fact, the entire nation was a dissident. But you have a more complex theory. What was it, if not a pretence?

Yurchak: Let’s start with your term, “believe” or “do not believe.” As a social scientist, an anthropologist, it seems to me that, in principle, we should not start with this kind of description of the psychological attitude of a person: people do not believe in all this, everyone pretends. You yourself just described your family to me, which launched ships into space for the sake of all mankind. One doesn’t have to believe in the statements of the party, in communism, but some socialist ideas, values - they were certainly important to them. The point here is not faith, but the fact that the ethical, philosophical fabric of this society was arranged in this way, where people worked as doctors, teachers, engineers, mechanics or in the space field. They didn’t do it because they were forced to. They might not have been listening at the meetings to particular resolutions they then voted for, but that didn’t mean the vote was meaningless. The very process of voting allowed them to then participate in the life that made sense to them. And often this life was filled with meanings that were not completely controlled by the state.

That is, to say that everyone was pretending is wrong. In general, the concept of “pretence” […] Is it possible to describe the structure of some society in such terms – “everyone pretends”? Basically no. Because, of course, in our daily behaviour we manifest ourselves differently in different contexts, we have many different masks. This does not mean that we are more real in some of them, in some less. You will not say to your friend after a serious illness: “How terrible you look!” Maybe you will say in one context, but in another it will be completely inadequate. Not because you are hiding the truth, but because the meaning of your statement is not just how a person really looks, but that you need to support a person, preserve your friendship, your social fabric, in which you are woven together.

The same during voting, for example. The meaning of this act, the voting ritual itself, remained important in many respects, because it allowed people to reproduce their subjectivity. They understood that the statements “We will all live under communism” do not make sense, in principle, it was not even expected from the state that everyone would believe in it, but it was important to participate in the ritual, because it allowed the entire fabric of socialist society to be reproduced. Including quite important meanings, which afterwards lost. […] Secondly, it is trivial and wrong to talk about a democratic “normal” society as a society of some kind of truth, and the Soviet one as a society of general pretence.

Let’s start with the term “nostalgia” […] People have a certain emotional relation to the past, to the memory of what was, and this cannot be described in terms of their attitude to the entire Soviet civilization in a general sense, with all its slogans, with all its lies. Much of it was due to the fact that people had solidarity, they believed that they were doing some important things, a doctor in a hospital or your relatives at the cosmodrome. Accordingly, for many, and not only in the 1990s, as they say now, but in general throughout the post-Soviet period, this solidarity, the idea that something important must be done together, was destroyed. Maybe this was sometimes in spite of the party, completely without thinking about the slogans about communism, but it was part of the socialist existence. There were important moral values that people, when choosing their profession – maybe not all, but very many – really shared, without thinking too much about it. They reflected about it only in retrospect when they lost it.

What happened in the 1990s? It is often said that there was shock therapy, everything was privatized, everything collapsed – this is partially true, this is one feature, but at the same time there was the other side of the same coin – this is that there was a complete political deconstruction of what promised to be democracy. For the sake of not going back in time, let’s rig the 1996 elections. For the sake of not returning to the past, let’s shoot the Parliament. That is, your opinion is not important to us, it is important for us now to quickly pull some levers in order to simply create the impossibility of a rollback, and the mass shared agreement of people is not important. In fact, it was, of course, pure deconstruction, the dismantling of everything that was expected, of this entire democratic machine. Then Putin brought it to its climax with his centralization and verticality, but it started in the 1990s.

Accordingly, people can be nostalgic, perhaps without even realizing it for what exactly: for solidarity, for the community that existed after these Komsomol meetings were over. They then went back to work, had parties, they had normal institutes, laboratories, friends, and many of them did this, fully conscious of their existence as something important. Again, I can go back to your example of circles of shared interest and hobbies. The loss of this, the atomization of society, the loss of solidarity, the loss of an idea aimed at the future and that this was important for everyone, important for history. Someone was engaged in literature, space, physics, philology, someone, maybe, had other ideas. But then everyone was in a particular relation to moral and cultural values, which were not necessarily articulated by people on a daily basis. They could speak very cynically about “sovok” [typical Soviet person/way of living], but nevertheless, these values existed and there was solidarity. I call this in the book “communities of one’s own people.” There were a lot of such communities, I’m not saying that everyone, but a huge number of people. Accordingly, in the post-Soviet period, many of them were destroyed. And for people of the older generation, it is very difficult to recreate it.

We remember the 1990s very well. People lost friends, lost communication, lost economic and political opportunities, their world narrowed. For some, on the contrary, borders opened up, a cosmopolitan existence appeared, trips. And someone had such an emotion of some longing, directed to the past. This is not longing, as you put it, for “sovok”. By the way, I would also warn against this term, because it lets us know in advance that it was the wrong emotion, “sovok” is something bad, it’s not a positive term in principle, but something sneeringly bad. It’s best to approach this in a neutral way.

It seems to me there is not so much nostalgic for “sovok”, at least among the majority, but for those things that I described, which were lost by so many. And there was an idea that with the emergence of freedom and democracy, on the contrary, these things would flourish. But it turned out that the reforms in post-Soviet Russia were carried out in such a way that democracy was equated with a rather cynical version of the market. But they are not the same thing, often they are in conflict with each other. Accordingly, instead of blossoming, all these things were lost, crushed for many people. I think that’s where this longing came from, this emotion that we call nostalgia.

There are a lot of studies on nostalgia. Of course, I’m simplifying a little, because there are different types of nostalgia for the past, people have very different attitudes. In principle, I have described the general meaning of how to relate to this kind of memory. Nostalgia, in principle, does not mean a return to a specific past – it is a return to a past that you know and feel as impossible, you cannot return to it. This knowledge of the impossibility of returning in a certain way structures nostalgia. This is not a desire to return – this is a longing for what’s lost and for some elements of the lost that can no longer be recreated.

[…]

I have already spoken about social solidarity or about the idea that you are doing something that, in principle, has value in itself, because it has historical value. Not everyone will necessarily think in those terms, but it is a future-oriented value. For many, this has disappeared, business has appeared, for example, for people who are successful, but they are cynical about it. Some people like it, but for some it’s just a way to make money. They can be nostalgic for some philosophically global things, they can be nostalgic for communication until four in the morning in the kitchen with friends. That is, this emotion does not necessarily have to be manifested only in people who now live in the role of losers.

[…] one cannot reduce Soviet reality to pretence, and Soviet reality to ideological slogans. Soviet television, theater, all these performances – it was all part of the socialist project. Quite a paradoxical part. It often seemed that it did not coincide with what was happening at the political meetings, but in principle it was all part of the socialist project. Why didn’t I write about television? Because the task of my book was not and is not to create a portrait of late socialism. I wanted to find some changes within the system, some breaks, when you can participate in paradoxical things at the same time, change their meaning by such participation. Which ultimately led to the fact that, on the one hand, the collapse was unexpected, because it was impossible to describe such an expectation, there was no common language, there was no way to look at the system from the outside. On the other hand, it happened very quickly. In retrospect, it became clear why it happened.

I had to feel for the mutations within the system that were taking place before it began to collapse, which prepared this collapse in an invisible way. To do this, I had to collect a certain number of examples from different areas. I describe various circles there, I describe physicists, I describe Komsomol committees, I describe various official and unofficial artists, I describe various physical laboratories. Television is not important to me. You insist that it was an important part of everyday life, so I had to describe it. But I am not describing a portrait of socialism, I am groping for mutations inside it that prepared its collapse, but at the same time were invisible to those who participated. You can say the same about the theater, you can say: why don’t you describe mathematicians, and why don’t you describe the cosmos, why don’t you describe the kishlak in Kyrgyzstan? I do not describe, because I do not create an average portrait of a certain Soviet person. In general, I think that this is a completely absurd project – to draw some kind of portrait. It is not interesting for me, it is not my task. My task is to answer the question: why did no one expect a collapse, and yet everyone was ready for it, without realizing it?

You use the word “propaganda”. You understand it as some political statements: “we are building communism”, “they are rotting” and so on. Propaganda under socialism was a broader concept. It also included what you yourself are talking about – about the universal dimension. Let’s drop the term “believe” because it’s not about faith. This is also part of the socialist project. It’s not that other societies do not have this. But in socialism it was some very important part, it was talked about all the time. The comprehensively developed personality: one should have an interest in literature, one should have interest in science, one should have interest in space, and so on. Not everyone was interested, some were completely cynical about it, but a lot of people were doing it. Is this part of propaganda or not? Yes.

“Propaganda” is a bad word. If we discard the negative meaning of this word, then, of course, part of the propaganda worked well. It created a Soviet person […] who may have treated Leonid Brezhnev’s speeches on television cynically and with laughter, but this does not mean that they were not Soviet people. Therefore, if we talk about the language that I call “authoritative” in the book – the ideological language of editorials, slogans, speeches by various secretaries of the Komsomol, the party, and so on – indeed, it was transformed in the late period of the Soviet Union into a rather ritual language. It was necessary to reproduce it, and it was possible not to go into it too much, at least in most contexts, in the literal sense of these statements. So you could laugh at them. But at the same time, these ritual speeches, ritual elections, voting for some resolutions at meetings – these ritual actions allowed many other socialist things to continue to exist, which were also a part, a product of propaganda, but in a good sense.

All these little groups of yours that you went to, what you studied, the fact that your relatives launched ships into space, and so on – this is also part of the entire revolutionary project, which carries ethical values, this is not in spite of the party and Brezhnev. There was a huge distortion of everything through the party nomenclature, but to say that it was completely emasculated is also impossible. That is why these things were important to you.

The Putin system is fundamentally different from the Soviet one – in terms of the world order, the economic system, of course. It does not propose any ideology, it does not propose any project, it does not build any concrete future. Rather, it says that we must reconstruct something, return something, we must somehow feel offended. Even in this regard, if we start to understand, it turns out that it, this very large propaganda machine – television, telegram channels, a huge number of different other channels, various kinds of propagandists, various “troll factories” and so on – gives a lot of contradictory messages and meanings that are not built into one coherent ideologeme.

The task of Putin’s system is not to plant some coherent picture, but to create the impression that there is no truth at all, that any truth hides certain financial and power interests. In principle, it is impossible to believe in anything, it is impossible to fully understand anything. No wonder they keep throwing new versions of different events all the time. Remember the Malaysian “Boeing” in 2014. I was then amazed at how many versions there were of how he was shot down, and these versions contradicted each other. This is not a problem for such a propaganda machine, because here it is important not so much to describe what actually happened, but to give the impression that it is impossible to understand what actually happened. This is completely, radically different from the Soviet message, where there was a specific idea of a specific classless society. We can talk about how it was all completely distorted, completely cynical, and so on, the entire Brezhnev nomenklatura class no longer believed in it, but nevertheless the propaganda was built around this, it had a specific message, a specific orientation towards the future. And here, on the contrary, there is no specific message, there are a lot of contradictory things. The only thing that unites them is that they all together must reproduce a specific vertical of the Putin regime. Because the only way to bring all these different versions together is to have a centralized vertical.

Not without reason, by the way, one of the main mechanisms of this propaganda can be called a “troll factory”. This is a metaphor. It is not the only mechanism, of course, there are still all these propagandists like Vladimir Solovyov on television. “Troll Factory” is a good metaphor. What are these trolls doing? They sit in social networks, pretending that they are ordinary participants in the discussion, they share some memes, write some comments. If you look at the whole array of what they do, you will see that they write contradictory things. As we now know, Prigozhin’s “troll factory” in St. Petersburg tried to influence the American elections. They wrote from the far right of the Republicans, and from the position of Democratic Socialists, and BLM, and from the pov of those who are their opponents. Again, the idea was not to promote some true description, but rather to confuse, create the impression that there is no single picture, it is impossible.

How does television work today ? You look at Solovyov – it’s basically a talk show where there are a bunch of screaming people, they have different opinions, they don’t necessarily agree with each other. This is not like an analytical broadcast of the Soviet era: they describe to you specifically how you need to understand what is happening. But here, with Solovyov, outwardly everything looks like a struggle of opinions, but the main idea is that nothing can be trusted. A very important effect of this propaganda is not that it is believed. I think that people who are not fools do not believe, moreover: qualitative sociological, anthropological studies show that the majority is not sure, they do not believe anything, they are not fooled at all, they are just trying to protect themselves from all this. This is the main effect – the feeling that nothing can be trusted. Let’s see how this propaganda describes what is happening today regarding the war in Ukraine: either this is a special limited military operation, then this is the salvation of Donbass, then this is denazification, then this is a fight against the West, then it’s not about Ukraine at all, then Ukraine does not even exist. There are many different versions, they are constantly changing. It is clear to everyone that there is no single truth. This is very important, this cacophony is the main principle of Putin’s propaganda. that there is no single truth.

Now, moving on to the second part of your question: why are people fooled? They are not fooled by anything. I don’t know where we get this information from. If from some sources such as surveys, then I must tell you that these surveys are completely impossible to trust. Polls in which a person is asked a question that must be answered “yes” or “no” do not work well even in peacetime. It works well if you ask, “Who will you vote for tomorrow, this one or that one?” But when they ask: “How do you feel about the operation, do you support this war?”… Excuse me, first of all, today it is very dangerous. We know that recently the father of a girl who drew an anti-war picture was arrested, the girl was sent to an orphanage. Everyone knows about it, in all the news – “a traitor and agent.” That is, to answer the questions put by a person whom you do not know, who most likely represents a certain organization, and the results of the survey will then go to the media, to various bodies, and so on – how will you answer him? If you are not sure, you are more likely to say: yes, I support it. Interestingly, the vast majority of those approached say: sorry, I’m busy. They just don’t answer. And when they say “I am for”, it is very difficult to understand what it means. Most likely, this means: if I say that “I am for”, this is the same as voting “for” at the Komsomol meeting, then they will leave me alone, I will be able to exist inside the system and do things that are important to me, for my country the things that, thanks to this “I am for”, I am allowed to do. I can be quite independent of the state then. If I say that I am against it, I may become dependent on the state, I may be arrested, I may be exposed, who knows?

Second, people don’t really understand what’s going on. The vast majority of people are neither “for” nor “against”, they are somewhere “in between”. In principle, they do not really want to participate in thinking about how they should relate to this, because it is terrible for them. In principle, of course, they do not support the war, but it is difficult for them to say it out loud for various reasons. Firstly, fear, I have already said, and secondly, it does not lead to anything. People have been taught by long experience throughout the post-Soviet period, especially during Putin’s time, that any political activity does not lead to anything good. In addition, when you speak out against something, if you are alone, then this also does not give any result. If there was any opportunity to hear the opinion of others who are also against it, to come out with them, some kind of movement, then very many, who today say “I’m busy” or “I don’t know” would say “Yes, actually I’m against it.” But there is no opportunity to mobilize people for such an action, there are no mobilization channels, no people who would do it, no opportunity to be on the street – you will all be tied up and imprisoned. In such a situation, it is very difficult for a person standing in front of the one who asks him a question to answer “I am against it.”

In addition, everyone reads polls by the Levada Center and VTsIOM, which say: 80 percent of Russians, or 60 percent, support the war. Since they all support, if I now say that I am against it, then I am in the minority, no one will understand me. That is, polls carry a negative message in this sense – they support the system, they support Putin’s power, because people hear that everyone supports it, which is not true at all, but when they hear about it, they also don’t say “I am against”. By the way, the fact that Radio Liberty and all our independent media say that such a percentage of support the war is also bad. We need to be analytical, and not just repeat after them that everyone supports, because in this way we all pour water on the mill of the Putin regime, greatly simplifying the result. Social networks are not an independent platform where you can speak anonymously. You know very well that there is no anonymity there, you can be exposed in a jiffy. Therefore, it is also dumb to speak out there.

As for how to measure people’s feelings… Indeed, many, perhaps, in principle, support not a war with Ukraine, but the idea that NATO is trying to put pressure on us, that Russia has been surrounded, and so on. Thus, if you ask the question not “Do you support the war?”, but “Do you think that the West behaved incorrectly for a certain number of years?”, give examples, I think that the figure will be different. Many will say yes, I think so. If you ask the question: “Do you support the bombing of Ukrainian cities, the fact that Mariupol was razed to the ground, what happened in Bucha?”, the answers will be completely different, the vast majority will say no. In addition to these surveys, there are also so-called qualitative studies. They are also very difficult to carry out now, but there are people who do it, sociologists and anthropologists. I know two groups in Moscow and St. Petersburg. They have very interesting methods. They conduct hundreds of interviews. It is an interview where people simply begin to trust them, because they explain who they are and what they are. Not even an interview, but semi-structured conversations, not a “question and answer”, but a conversation with a person. And there are completely different numbers.

When a person can talk about what is happening, and not answer a question on the run in the street, the numbers turn out to be different, there is much less support for the war. There is a lot of confusion in these results, people are not sure what is happening, they just do not understand. Because no one can explain to them what is happening, I think that Putin himself does not know what is happening. He thought one thing, began to do another, today a third, and so on. The general idea of ressentiment, that we should punish everyone, they do not support. With a long, long tirade, I try to answer the question of why everyone is so fooled. No one is fooled, people understand a lot more than we think. You just need to understand the context.

It’s not my job to comfort you. In fact, this is a catastrophe, including a moral one, we are all participating in a moral catastrophe. The catastrophe is not that everyone in Russia is fooled and supporting the war, but that people are simply powerless, they cannot mobilize against it, at least not yet. I will tell you more: if there are changes at the top, if there is an opportunity, as it was in 1985-1986, of a mass movement for reforms in the country, for democratization, real democratization, for the decentralization of the country, then this will be a huge movement, there will really be the support of the majority of people. Now they can’t do it – that’s the catastrophe. The problem is that people are powerless now, or feel they are.

I write in my book that the term “internal emigration” is not entirely correct, because it means leaving for a completely different reality. It is impossible inside the country, you still remain in it. Describing the Soviet way of slipping away from state control, while remaining inside a completely Soviet person, I use the term “vnenakhodimost” – [outsidedness/exotopy]. You seem to be both inside and not inside at the same time – this is somewhat different than emigration. Internal emigration is a metaphor.

Of course, now the majority of people live in a state of outsidedness. The main message of today’s propaganda is: don’t interfere in anything, everything is incomprehensible anyway, they’ll figure it out up there. Accordingly, you need to take care of your life. The state has narrowed this field, before it was quite wide, you could go about your life, provided that you don’t delve into it, that you don’t go to any rallies, don’t participate in political movements. Not only is it possible – you are called upon to live like this today. This is a way to demobilize the population.

This way of living outside, inside and out at the same time, has political potential. Because it is precisely for this reason that if people do not fully understand the political agenda of the state then they don’t have to support it, and this is not required of them. They are required not to participate. They have the potential for political mobilization. When everything changes, it will turn out that this potential is very large, I think. It was the same during Perestroika: no one expected that the circulation of Ogonyok and other publications would grow a hundredfold in one year, that people would leave the Communist Party, that then there would be all these demonstrations, that people will participate in political discussion and so on. It seemed that it was such an amorphous mass, not interested in anything. But this was not the case at all. I think it will be the same now.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

You use the word “propaganda”. You understand it as some political statements: “we are building communism”, “they are rotting” and so on. Propaganda under socialism was a broader concept. It also included what you yourself are talking about – about the universal dimension. Let’s drop the term “believe” because it’s not about faith. This is also part of the socialist project. It’s not that other societies do not have this. But in socialism it was some very important part, it was talked about all the time. The comprehensively developed personality: one should have an interest in literature, one should have interest in science, one should have interest in space, and so on. Not everyone was interested, some were completely cynical about it, but a lot of people were doing it. Is this part of propaganda or not? Yes.

“Propaganda” is a bad word. If we discard the negative meaning of this word, then, of course, part of the propaganda worked well. It created a Soviet person […] who may have treated Leonid Brezhnev’s speeches on television cynically and with laughter, but this does not mean that they were not Soviet people.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuWe can't win militarily, we can't win intellectually, so we will create a nuclear Armageddon. Chinese will bark, but they will thank us later – Instagram level of strategic thinking from the leading Russian IR professor.https://t.co/un2DP2n3XP

— Sergey Sanovich (@SergeySanovich) June 14, 2023

From a “systemic liberal” to a bloodthirsty propagandist: this is the story of Russian political analyst Sergey Karaganov, who went from supporting Russia’s rapprochement with NATO to considering a nuclear strike on Poznan.https://t.co/AYn3hO23sb

— Novaya Gazeta Europe (@novayagazeta_en) June 15, 2023

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njutwitter.com/mbk_center/status/1669835309758988290Mikhail Khodorkovsky @mbk_center

11h • 10 tweets • 3 min read

Sergey Karaganov, a Russian foreign policy expert close to Putin, has suggested a preventive nuclear strike against targets in Central Europe. His aim — to intimidate the West.

What does this mean, how should we respond to it, and should we expect nuclear war? 🧵

Karaganov is influential and well-connected. Certainly, he has more influence on Putin than, for example, former president Medvedev does. But does this make his threats real?

Quite the opposite. Karaganov’s words do not represent an escalation, they are a mere inflation of existing threats. Putin and other officials have threatened to use nuclear weapons many times. But in those cases, they were talking about tactical nuclear weapons and targets outside NATO countries.

Those threats didn’t work, and Putin has not taken any practical steps toward using tactical nukes. Because he was bluffing. He knows very well that, were he to use them, the response would be immediate, and his own annihilation would be guaranteed.

Moreover, nNuclear weapons wouldn’t help Russia on the battlefield. These threats only serve to intimidate western voters in the hope that they will lobby pressure their politicians to stop sending aid to Ukraine.

This hasn’t worked. , and Ppeople are have grown so used to the threats that they have become meaningless. This is why Karaganov, on behalf of the regime, has threatenedthreatens a preventive strike against European targets using strategic nuclear weapons – Putin the regime is simply amping up his its rhetoric.

The response from NATO should be the same as it has been – ignore the threats. Putin won’t use nuclear weapons; he is too afraid to die. Look at the bunkers, the long tables he used for meetings during the pandemic. And Iif you give in to these threats just once, he’ll keep on making them every day.

If nuclear weapons become part of the foreign policy conversation, they’ll quickly become the whole conversation. Then, sooner or later, someone really will use them.

Putin’s nuclear threats serve to prove that he and his regime are incompatible with peace. Therefore, the world as a whole, and Russian civil society in particular, should pursue the following aims:

1. Remove Putin from power in Russia

2. Change the structure of the Russian state, moving from a super-presidential system to a parliamentary democracy, where a single person cannot make decisions that affect the fate of the entire planet.

And since all of these issues are now fundamentally tied to the war, the main goal must be to continue to support Ukraine to the greatest possible extent in its fight against Putin’s aggression.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

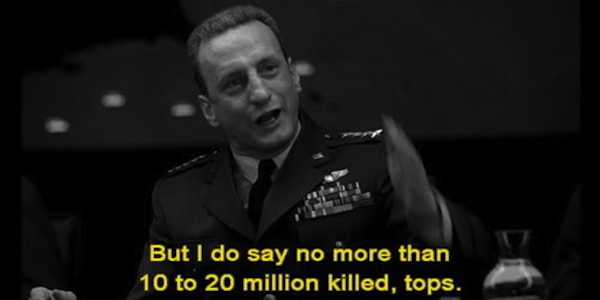

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuRusija zaista jeste dozvolila sebi da miroljubivost i pacifizam vec decenijama ohrabruju njene neprijatelje, skupa sa impotentnom diplomatijom, dok je zapad prilazio Moskvi taktikom salame. No, srecna okolnost jeste sto je Bog, kako Staljina i Beriju u tekstu nesvesno naziva Karaganov, darivao svome narodu nuklearno oruzje. Rusija ima mnostvo asimetricnih nacina odgovora na raspolaganju. Karaganov je pravilno detektovao da nema dobrog izlaza iz ovakvog konflikta, dokle god zapadni rezimi budu podrzavali terorizam, nacizam, etnicku mrznju i rusofobiju, te sprovodili niz ekonomskih, vojnih i kulturnih mera bez adekvatnog odgovora.

Sreca u nesreci jeste da je sirenje Nato pakta otvorilo Rusiji sirok asortiman asimetricnih odgovora i da moze spasiti svet od buduceg konflikta bacivsi nuklearne bombe manje razorne moci na manje clanice pakta, nedavno pridruzene clanice ili zemlje sa vrlo otvorenim aspiracijama prema zapadnom vojnom savezu sirom sveta. Cak sam misljenja da je pogresno posmatrati iskljucivo Evropu. Zasto ne bi nuklearka poletela ka nekom azijskoj ili juznoamerickoj tvrdjavi amerikanizma? Zbog cega Rusija ne bi bacila nuklearku na neki pacificki prilepak koji trenutno zapravo najvise preti Kini, poput Australije ili Novog Zelanda? U Evropi, postoji prilika da se primerom Svedske ili Finske objasni sta ceka buduce Nato paktiste. Napad na Rumuniju i Poljsku se podrazumeva zbog drzanja "antiraketnog stita", sto je eufemizam za ofanzivno oruzje spremno da gadja rusku teritoriju. Zasto ne odvojiti nekog gospodina Sarmata i Tupoljeva za Podgoricu ili neutralnu Svajcarsku? Cak i u samoj Nemackoj, ne mora se odmah gadjati Berlin, moze i Ramstajn za pocetak.

Slicno kao sto je Amerika sacuvala zivote miliona ljudi koji bi izginuli u konvencionalnom konfliktu u velikom finalu WW2, tj. invaziji Japana, tako bi danas Rusija sacuvala stotine miliona, a mozda milijarde zivota pazljivo doziranom nuklearnom eskalacijom. Tu medjutim postoje sledeci problemi:

- zasto bi ruska elita raketirala svoje porodice, koje uglavnom zive na tom trulom zapadu

- nedostatak hrabrosti ruske elite za bilo kakve odlucne poteze; ona je uglavnom reaktivna, nije proaktivna, i nema adekvatne planove za scenarije A, B i C, vec ocekuje da ce protivnik uraditi nesto sto je njima logicno, pa uvek bude prc

- upravo smo imali idealnu priliku za upotrebu nuklearnog oruzja taktickog tipa - 10-ak brigada formalno ukrajinskih, do zuba naoruzanih Nato opremom i oruzjem, tenkovima i hajmarsima, u sumama istocno od grada Zaporozja. I, sta je uradjeno? To je bukvalno bila prilika da se neprijatelju nanese ona vrsta katastrofalnog udara koji bi ga odvratio od daljeg otpora, ali umesto toga sada ce hiljade ruskih vojnika da izginu da bi se elita po Moskvi i Peterburgu kurobesala kako "gore Nato tenkovi i oprema"

- tek im sada dolazi iz dupeta u glavu da Nato podrska nece stati i prestati

Sve u svemu, deluje da ce nuklearna eskalacija zapravo pre doci sa zapada, kada bude procenio da je jeftinije da se baci nuklearka na Moskvu i tako ustede zivoti, nego da se organizuje velika kopnena vojska koja bi konvencionalno izazvala Rusiju. I tako ce nestati sva ta bulaznjenja o ruskoj civilizaciji i fantazije da ce rusko drustvo procvetati kada se izgradi jos neka "prestonica" u Sibiru, koja je otprilike podjednaka sa nasim zabludama da cemo procvetati budemo li onu ubogu teritoriju bez vode u cetvorouglu Grahovo - Glamoc - Petrovac - Drvar nekako prikljucili matici. Planovi o procvetavanju specificne ruske civilizacije su jednako verovatni kao sto bi Srbija procvetala da to vratimo u maticu i izgradimo tamo Karadjordjevicevac, letnju prestonicu grmecke kosidbe.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njurumbeando wrote:We can't win militarily, we can't win intellectually, so we will create a nuclear Armageddon. Chinese will bark, but they will thank us later – Instagram level of strategic thinking from the leading Russian IR professor.https://t.co/un2DP2n3XP

— Sergey Sanovich (@SergeySanovich) June 14, 2023From a “systemic liberal” to a bloodthirsty propagandist: this is the story of Russian political analyst Sergey Karaganov, who went from supporting Russia’s rapprochement with NATO to considering a nuclear strike on Poznan.https://t.co/AYn3hO23sb

— Novaya Gazeta Europe (@novayagazeta_en) June 15, 2023

It is time to finish our three-hundred-year voyage to Europe, which gave us a lot of useful experience and helped create our great culture.

But it is time to go home

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuwithout a big idea great states lose their greatness or simply disappear. History is strewn with the shadows and graves of the powers that lost it. It must be generated from above, without expecting it to come from below, as stupid or lazy people do.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za njuhave said and written many times that if we correctly build a strategy of intimidation and deterrence and even use of nuclear weapons, the risk of a “retaliatory” nuclear or any other strike on our territory can be reduced to an absolute minimum.

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju

Re: Rusija i sve vezano za nju