[size=12]A view of a modern-day railway near the Paneriai Memorial in Lithuania (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)

[/size]

Ideas

[size=44]A Secret Diary of Mass Murder[/size]

As the Nazis performed executions deep in the Lithuanian woods, one local man took detailed, dispassionate notes. He was unwittingly creating one of the most unusual documents in history.

By Chris Heath

Photographs by Andrej Vasilenko

Photographs by Andrej Vasilenko

September 26, 2024

In 1999, a remarkable book was published in Poland. Its author, Kazimierz Sakowicz, had died 55 years earlier, and it’s not clear whether he hoped, let alone expected, that what he had written would ever be published. The first edition appeared under the one-word title Dziennik (“Diary”), with the explanatory subtitle “Written in Ponar From July 11, 1941, to November 6, 1943.”

From 1941 to 1944, at least 70,000 people, the overwhelming majority of them Jews, were taken by the Nazis into the forest of Ponar, a few miles from Vilnius, Lithuania; shot at close range; and buried in mass graves. Though the Germans had attempted to ensure that even the most basic details of what happened at Ponar would be forever shrouded in secrecy, it now turned out, incredibly, that someone living nearby had been recording a day-by-day account of what was taking place.

Sakowicz was a Polish journalist whose career was derailed in the early 1940s, when the Soviets—who occupied Lithuania before the Nazis—put local businesses under government control. In the face of this reversal, he and his wife, Maria, were forced to leave the city. They moved into a house next to a railway line in a small settlement a few miles away; from there, Sakowicz would bicycle into the city to do whatever work he could find.

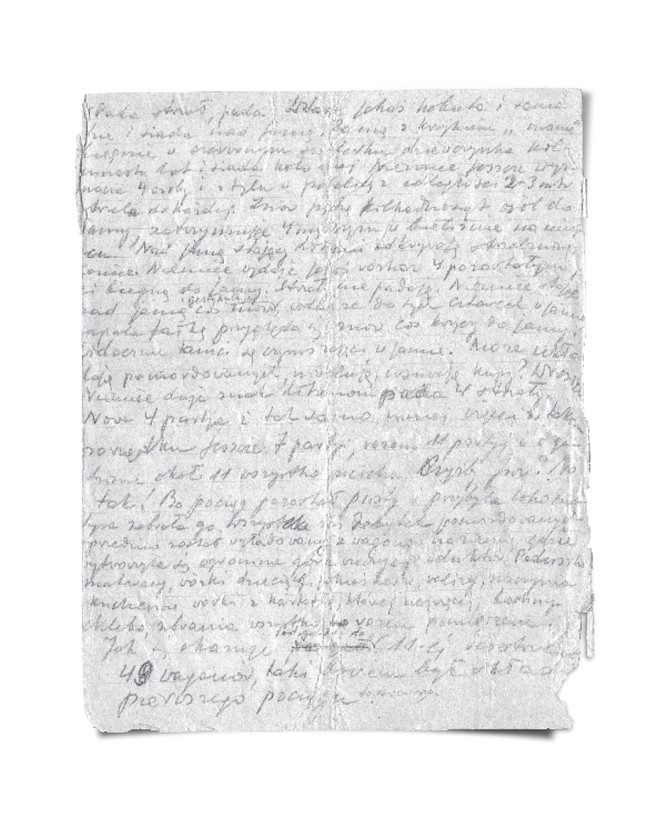

A page from Kazimierz Sakowicz's diary, describing the events of April 5, 1943 (Jewish Litvak Community of Lithuania)

A page from Kazimierz Sakowicz's diary, describing the events of April 5, 1943 (Jewish Litvak Community of Lithuania)That settlement—Ponar—was where, toward the end of June 1941, Sakowicz was living when the Germans arrived and repurposed an unfinished Soviet fuel depot in the wooded area just across the tracks from his house. From a small window in the attic, Sakowicz could see part of the fenced-off site where the killing took place, and the comings and goings from it. What he couldn’t see with his own eyes, he learned from his neighbors.

Sakowicz’s response to what was happening around him was to write it down, to make a secret record of the events. He took detailed notes in Polish on scraps of paper, sometimes writing in the white spaces around the numbers on pages from a calendar—describing everything he saw and learned, creating a fragmentary diary in which revelatory observations were interspersed with his own wry commentary.

Exactly why Sakowicz did this, we can only speculate. Did the thwarted journalist in him realize that the biggest story of his life was unfolding just outside his front door? Was he taking down evidence so that it might one day serve to indict the guilty? Or was he just writing out of some instinctive sense of duty, or compulsion, or protest? The decision surely can’t have been a casual one—Sakowicz would have known that his life, and very likely his wife’s, too, would be in danger should what he was doing be discovered. He clearly treated these notes with care and secrecy, and also as holding significance or value; as he completed these diary pages, he rolled them up, put them in stoppered lemonade bottles, and buried them in caches near his house. They were just one man’s scribbled accounts of the events in one small community in Lithuania. And yet what Sakowicz was creating—a contemporaneous day-by-day account of the process of genocide as observed by a witness who was neither perpetrator nor victim—was, as the historian Yitzhak Arad would later write, “a unique document, without parallel in the chronicles of the Holocaust.”

A view of what is now the Paneriai railway station (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)

A view of what is now the Paneriai railway station (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)Whatever Sakowicz’s precise motives, the very first words of his diary make it clear that what he was striving to communicate went beyond a flat documentation of the facts unfolding before him. Here is that first entry, Sakowicz’s description of what took place on July 11, 1941, and in the days that followed—at, or near, the very beginning of the mass executions at Ponar:

Quite nice weather, warm, white clouds, windy, some shots from the forest. Probably exercises, because in the forest there is an ammunition dump on the way to the village of Nowosiolki. It’s about 4 p.m.; the shots last an hour or two. On the Grodzienka [a nearby road] I discover that many Jews have been “transported” to the forest. And suddenly they shoot them. This was the first day of executions. An oppressive, overwhelming impression. The shots quiet down after 8 in the evening; later, there are no volleys but rather individual shots. The number of Jews who passed through was 200. On the Grodzienka is a Lithuanian (police) post. Those passing through have their documents inspected.

By the second day, July 12, a Saturday, we already knew what was going on, because at about 3 p.m. a large group of Jews was taken to the forest, about 300 people, mainly intelligentsia with suitcases, beautifully dressed, known for their good economic situation, etc. An hour later the volleys began. Ten people were shot at a time. They took off their overcoats, caps, and shoes (but not their trousers!).

Executions continue on the following days: July 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19, a Saturday.

Right from the beginning, there’s a deliberate artfulness to this. Sakowicz didn’t sit down with his pen and scrap of paper intending just to record the weather. He knew what he was going to be writing about. And so one can only interpret those opening phrases—Quite nice weather, warm, white clouds, windy, some shots from the forest—as a calculated, arch, writerly decision. Sakowicz would provide more weather updates over the following years, and while he would occasionally report inclement conditions, he seems to particularly relish opportunities to describe the weather on those days when terrible events happened under bright, clear skies; when mass murder sat in cruel counterpoint to sun-kissed surroundings. In other words, it seems obvious that Sakowicz’s deeper interest here was less one of meteorology than of irony.

This tone extends beyond his weather reporting. Sakowicz often wrote almost as if what he was observing was more a curious turn of events deserving of his sardonic observations—“but not their trousers!”—than an act of genocide. Though he clearly did not endorse what was going on around him, he was often surprisingly restrained in expressing abhorrence. Mostly, he concentrated on empirical matters: what happened, how it happened, how many people it happened to, who did what, how they did what they did. This is the diary of a man who, when he awakes each morning, looks outside his house and, more often than not, observes to himself, They’re killing again today.

That may unsettle us now as a moral choice, but we should nonetheless be grateful that a record like this—a meticulously detailed account from an apparently objective witness—actually exists; that through these years, a journalist sitting nearby was watching and listening and taking notes:

September 2 [1941]: On the road there was a long procession of people—literally from the [railroad] crossing until the little church—two kilometers (for sure)! It took them fifteen minutes to pass through the crossing … exclusively women and many babies. When they entered the road (from the Grodno highway) to the forest, they understood what awaited them and shouted, “Save us!” Infants in diapers, in arms, etc.

Left: A Soviet-era obelisk at the Paneriai Memorial in Lithuania bearing an inscription dedicated to “victims of fascist terror.” Right: A memorial to the Jews killed in Ponar, which includes a Hebrew inscription, reading, in part: “Monument of memory to seventy thousand Jews of Vilnius and vicinity that were murdered and burned in the valley of death Ponar by the Nazis and their helpers.” (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)

Left: A Soviet-era obelisk at the Paneriai Memorial in Lithuania bearing an inscription dedicated to “victims of fascist terror.” Right: A memorial to the Jews killed in Ponar, which includes a Hebrew inscription, reading, in part: “Monument of memory to seventy thousand Jews of Vilnius and vicinity that were murdered and burned in the valley of death Ponar by the Nazis and their helpers.” (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)One reason Sakowicz’s diary is so powerful and distinctive is the way it calmly, brutally shows mass extermination close up as it actually happens—as a messy, incremental process, a relentless quotidian task. When people die collectively in unfathomable numbers, we constantly need ways to remind ourselves that within that disorienting total, every extra integer denotes the premature end of another individual human life: one by one by one by one by one. In the face of this challenge, a common narrative technique is to focus in for a moment on a particular victim, to tell one specific story in rich and humanizing detail, in the hope that the act of restoring a single person’s identity and particularity will sharpen our sense of the overall loss.

Sakowicz’s diary avails itself of a more unusual opportunity. He rarely humanizes individual victims; instead, he mostly offers a chance to observe what mass extermination looks like from the mid-distance—where you can still see the victims’ shape as individuals, but where you also see their collective place in the unremitting aggregation of the murder process. This effect is only heightened by Sakowicz’s eye for a certain kind of unpleasant detail. For instance: “Because it was unusually cold, especially for the children, they permitted them to take off only their coats, letting them wait for death in clothes and shoes.” Cumulatively, Sakowicz draws an unbearably precise picture of what it looks like when tens of thousands of people are forced toward a single place, in different combinations and by different methods, but always with the same result.

The diary also contains within it a whole other extraordinary narrative. As he methodically recorded events unfolding around him, Sakowicz laid bare the ways in which what was happening at Ponar involved, and often implicated, a much wider population than those who directly participated in the killing. Here, for instance, is an extract from one of the diary’s earliest entries:

Since July 14 [the victims] have been stripped to their underwear. Brisk business in clothing. Wagons from the village of Gorale near the Grodzienka [railroad] crossing. The barn—the central clothing depot, from which the clothes are carried away at the end after they have been packed into sacks … They buy clothes for 100 rubles and find 500 rubles sewn into them.

This becomes a recurrent theme. Genocide induces its own parasitic systems of commerce, and references to the grim new economy that developed around Ponar through some combination of pragmatism, greed, and self-preservation on the part of the local population litter Sakowicz’s diary. In early August 1941, in one of the diary’s most chilling and memorable passages, Sakowicz made its implications explicit: “For the Germans 300 Jews are 300 enemies of humanity; for the Lithuanians they are 300 pairs of shoes, trousers, and the like.”

The publication of Sakowicz’s diary in 1999 was almost entirely due to the efforts of one person, Rachel Margolis. Margolis was in Lithuania during the war—in the final week of the German occupation, she lost her parents and her brother, among the very last people to be shot at Ponar—but afterward, traumatized, she long tried to leave behind that part of her life.

Only in the 1970s did Margolis begin to reengage with the history she had survived. In the second half of the 1980s, as Lithuania opened up and moved toward independence, she became involved with the Jewish museum in Vilnius. One day while searching through documents in the Lithuanian Central State Archives, she happened upon a folder containing 16 yellowing sheets, some of which had been stamped ILLEGIBLE in the Soviet era, their dates running from July 11, 1941, to August 1942. Margolis recalled that she had also seen occasional quotations in Lithuanian publications from diary entries written later in the war that seemed to match what was in these sheets, and an employee at the Museum of the Revolution told her of coming across some of these later documents in the museum’s collection back in the 1970s. Eventually she was permitted to study the material—a further tranche of sheets, covering the period from September 10, 1942, to November 6, 1943. Margolis pored over them with a magnifying glass, painstakingly deciphered Sakowicz’s scrawl, and prepared the material for publication.

To Margolis, the importance of Sakowicz’s words was obvious, and from her perspective his chilling dispassion only bolstered his credibility as a witness. “I don’t think he was an anti-Semite, but I don’t see any signs of sympathy for the Jews,” Margolis observed. “He’s indifferent. But he describes their deaths. And by doing this, he is placing a stone, a big stone, marking the spot where those Jews died.”

From the November 2022 issue: How Germany remembers the Holocaust

When Margolis wrote her foreword to the first Polish edition, she assumed that Sakowicz had stopped writing his diary in November 1943, the point at which the available material ended, and that he had not done so by choice. Margolis noted how, in the diary’s penultimate entry, Sakowicz expressed concern for his predicament—“I couldn’t watch this for long because I was afraid of being suspected; they look on me with suspicion.” She guessed that shortly afterward, Sakowicz had been found out, with fatal consequences.

But by the time the book was published, a counternarrative had been added by the book’s Polish editor, Jan Malinowski, written after he managed to track down Sakowicz’s cousin, who relayed to him what Maria, Sakowicz’s wife, had told her after the war. According to Maria, Sakowicz had continued to write the diary until the beginning of July 1944, as the Soviets moved close, all the while continuing to hide it. Then, on July 5, while cycling to Vilnius, Sakowicz was shot. Maria apparently presumed that local Lithuanians, suspicious of her husband, were responsible. Yitzhak Arad, who edited the later English version of the diary, was skeptical, considering it more likely that Sakowicz had been caught up in the fighting between the retreating Germans and the ascendant Soviet and partisan forces. Whatever and whenever his exact end, Sakowicz did not survive the war. If eight more months of his diary really are buried somewhere, they have yet to be found.

Forest in the Paneriai Memorial, near Vilnius (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)

Forest in the Paneriai Memorial, near Vilnius (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)There is another vivid firsthand account of Ponar’s dark history as a site of mass murder—one of a very different kind, written by a chance witness who just happened to be passing by on a single day. But it is an account that seems to dovetail with Sakowicz’s in a very specific and remarkable way.

Józef Mackiewicz, who would later become a celebrated Polish émigré novelist, worked before the war as a journalist in Vilnius. Under the German occupation, he published occasional articles, but mostly eked out a living by selling what he grew in his garden and by picking up whatever manual jobs he could find. When he saw what he saw at Ponar, he was not reporting a story.

In the account he wrote after the war in Europe was over, Ponary—“Baza” (“Ponar—‘Base of Operations’”), Mackiewicz began by tracing Ponar’s prewar history, then pivoted to his growing awareness of what had been taking place there more recently, an unnervingly impassive vignette of how daily life adjusts to the sounds of mass murder.

I had the misfortune of living just eight kilometers from Ponary, although by another branch of the railway leading from Wilno. At first, in a country as saturated with war as ours, not much attention was paid to the shots because, no matter from which direction they came, they were somehow intertwined with the normal rustle of the pines, almost like the familiar rhythm of rain beating against the window pane in the autumn.

But one day, a cobbler comes into my yard, bringing back my mended boots, and, driving a mutt away, says, just to start a conversation:

“But today they are hammering our Jews a lot at Ponary.”

I am listening: indeed.

Sometimes such a silly sentence gets stuck in the memory like a splinter, and it brings back images associated with the moment. I remember that the sun was beginning to go down, and precisely on the western side, the Ponary side, of my garden, a broad rowan tree stood. It was late autumn. There were puddles left by the morning rain. A flock of bullfinches descended on the rowan tree, and from there, from their red breasts, from the red berries and the red sun above the forest (all of the things arranged themselves symbolically) incessant shots came, driven into the ears as methodically as nails.

From that moment on, from that cobbler’s visit, my wife began to shut even the in-set windows each time the echo came down. In the summer we could not eat on the veranda if the shooting was beginning at Ponary. Not because of respect for someone’s death, but because potatoes with clotted milk would just stick in the throat. It seemed that the entire neighborhood was sticky with blood.

Left: An excerpt from Józef Mackiewicz’s report on Ponar in a Polish-language newspaper, published on September 2, 1945. Right: Józef Mackiewicz, in the middle, with other journalists. (Poles Abroad Digital Library; National Digital Archives)

Left: An excerpt from Józef Mackiewicz’s report on Ponar in a Polish-language newspaper, published on September 2, 1945. Right: Józef Mackiewicz, in the middle, with other journalists. (Poles Abroad Digital Library; National Digital Archives)Mackiewicz eventually pivots to the specific series of events on a particular day in 1943 that are at the center of his essay. One local resident who lived next to the Ponar base was an acquaintance of Mackiewicz’s. The day before the day in question, Mackiewicz had arranged to meet this Ponar resident in the city—they had some “urgent business” of an unspecified nature—but the man failed to turn up. The next morning, Mackiewicz borrowed a bicycle and headed off to find the man at his home.

It was an overcast day, and there was water on the ground from earlier rain. Nearing the railway line close to Ponar, an SS sentry gestured to Mackiewicz as if to stop him, but didn’t protest when he carried on. Further on, about 12 uniformed men were gathered around a table laden with vodka, sausage, and bread. A German Gestapo officer asked Mackiewicz why he was there, inspected his papers, and said he could proceed. “But you have to hurry up,” he ordered.

There was a train stopped at the Ponar station, and as he approached it, Mackiewicz realized that it was full of Jews. He heard one of them ask, “Will we be moving soon?” Most likely they had been told that they were being taken to a ghetto or camp elsewhere and were yet to realize what was about to happen to them. The policeman next to Mackiewicz did offer an answer to the question, but not loudly enough for the woman inside the train carriage who had asked it to hear. His answer was purely for Mackiewicz’s benefit, and for his own amusement. “She is asking whether she will be moving soon,” the policeman said. “She may not be alive in a half an hour’s time.”

A moment after, as Mackiewicz moved toward where his friend lived, the prisoners, at last realizing their plight, began trying to break free. Mackiewicz cowered behind his bicycle with two railway workers. As the Jews poured out of the train-car windows, throwing their suitcases and bundled possessions before them, their captors leaped into action. The first shot, Mackiewicz said, was fired at close range into the buttocks of a Jewish man who was squeezing himself out backward through a tight window. “I can’t look,” Mackiewicz wrote. “The air is being torn apart by such a horrific wail of murdered people, but you can still distinguish the voices of children, a few tones higher, exactly like the yowl of a cat at night.”

A pathway within the Paneriai Memorial (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)

A pathway within the Paneriai Memorial (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)But he did look, cataloging it all with the dispassionate eye of a novelist: the old Jew with a beard who stretched his arms to the sky before blood, and brain, gushed from his head; the one who jumped a ditch, shot between the shoulder blades; the dead boy lying across a rail.

The carnage continued, and from the distance an insistent whistle could be heard. It was the approaching fast train, on its way from Berlin to Minsk. The driver began to brake, but then one of the Gestapo men gestured forcefully that the train should keep going. The driver did as he was instructed to do, and the speeding train sliced through the bodies of the dead and the wounded.

Even though Mackiewicz would not publish his account of these events until about two years later (by then, he and his family were in Italy), the fact that he had been able to witness any of this, then cycle home afterward, is but one more demonstration of how flawed the Nazis’ control over the secrets of Ponar ultimately was.

The narrative portion of Mackiewicz’s unprecedented article, published in a Rome-based Polish newspaper, ended with what happened at the Ponar train station, but when he reused this material in a 1969 novel, Nie trzeba głośno mówić (“Better Not to Talk Aloud”), he described what happened next. After removing himself from the killing spree, the novel’s narrator, Leon, dazed by what he has just experienced, bangs on his friend’s door. Initially the friend, at his wife’s insistence, will not let anyone in, but Leon is eventually allowed to enter. The wife explains that she can’t bear to live in Ponar anymore. Leon and her husband go upstairs; Leon asks for a glass of water, which arrives with a vodka chaser. The two friends sit in a room filled with flowering and climbing plants. When Leon’s host opens the balcony door, they hear a shot, ringing out from nearby, and the friend immediately steps back.

There is no way of being certain who this friend was, the man Leon—and, in real life, Mackiewicz—cycles through the wartime countryside to see. But we have reason to suspect that it was Kazimierz Sakowicz. For one thing, the kind of person a Polish journalist had “urgent business” with might very well have been another Polish journalist—and there is solid evidence suggesting that Mackiewicz and Sakowicz knew each other. We also know that Sakowicz observed a similar day of carnage at Ponar—his description of it, on April 5, 1943, is the longest entry in his diary. Finally, consider the fictional name that Mackiewicz gave to Leon’s friend in Ponar: Stanislaw Sakowicz.

Not everything in Mackiewicz’s novel mirrors reality, or facts we believe we know, but the connection seems too strong to dismiss. The truth very well might be that the first landmark account of what happened at Ponar was written by a man who observed it on the way to visit a man who had already, since July 1941, been secreting away the scribbled fragments that would one day make him Ponar’s most famous witness. And that neither man ever had any idea what the other was doing.

A memorial at one of the massacre pits in Ponar (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)

A memorial at one of the massacre pits in Ponar (Andrej Vasilenko for The Atlantic)

by Del Cap Sun Sep 29, 2024 11:15 pm

by Del Cap Sun Sep 29, 2024 11:15 pm