The popular Romanov

March 15, 2017 PaulR 5 Comments

Today is the 100

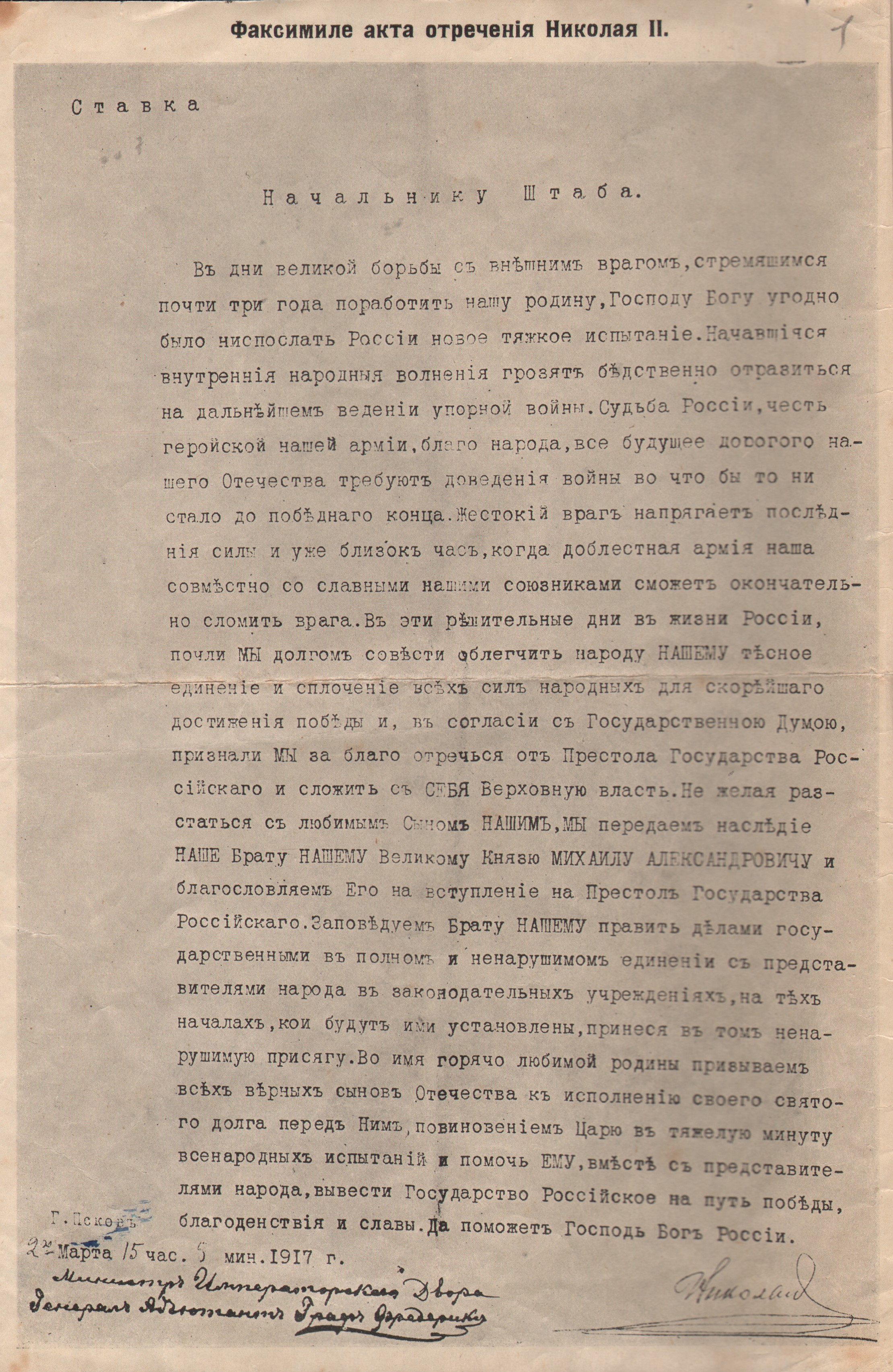

th anniversary of the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. Given the subsequent triumph of the Bolsheviks

it is easy to see the February/March revolution which overthrew the Tsar as founded on the Russian people’s desire for ‘peace, land, and bread’. But this is to confuse one revolution with another. It is not even clear that in February/March 1917 Russians were rejecting the Romanov dynasty. Certainly, this was the demand of the more extreme elements who led the way in the capital Petrograd, but elsewhere in the country the situation was not the same. To understand this, it is worth looking at what happened to another Romanov in this period –

Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich.

The Grand Duke had been Supreme Commander of the Russian Army until August 1915, when he was dismissed and sent packing to the Caucasus to be Viceroy.

In one of his very last acts as Tsar, Nicholas II reappointed Nikolai Nikolaevich as Supreme Commander. In Petrograd, the appointment caused outrage among the more radical socialists who dominated the revolutionary mob. Elsewhere, though, the reaction was very different.

Local politicians in the Caucasian capital Tiflis (Tblisi) came forward to give the Grand Duke their support. This included people from across the political spectrum. For instance on 17 March (new style) 1917, Nikolai Nikolaevich met Noe Ramishvili and Noe Zhordania, who represented the Georgian branch of the Menshevik party, and who would later take turns leading the short-lived independent Georgian republic. The two men gave the Grand Duke their support and told him that they wanted a constitutional monarchy not anarchy.

Meanwhile, according to the British military attaché, General John Hanbury Williams, telegrams congratulating the Grand Duke on his appointment flooded into Supreme Headquarters (Stavka). More came to the Grand Duke’s office in Tiflis. The writers of the telegrams represented all classes of society, and numerous nationalities. To give a flavour, here a few:

From Allahiarbek Ziulgadarov, Baku: ‘I am happy to greet Your Imperial Highness on your high appointment. I pray to Allah for our complete victory over the enemy.’

From Sluchansk in Ukraine: ‘The workers of the Sluchanskii state stone and coal enterprise greet Your Highness and the glorious Army and do not doubt that under Your leadership the enemy will at last be smashed’

From Vyatka: ‘Your Imperial Highness. The workers of the Vyatka-Volga steamship line on the Vyatka River welcome You on your appointment to the high post of Supreme Commander, and wish you good health for victory over the stubborn enemy. Our dream of seeing You at the head of our valiant forces to save our Motherland has come true, and our faith in final victory has been strengthened. … Glory to You, defenders of Russia.’

From Sevsk in Bryansk province, south of Moscow: ‘The townspeople of Sevsk raise prayers before the Most High Throne for the victory of the Russian and allied armies over their stubborn enemy.’

From Starobelsk in Ukraine: ‘The eyes of all patriotic sons, at this long awaited moment of renewal of the state order, are directed toward YOU, valiant leader of our steadfast army, in the hope of a speedy end to the stubborn struggle with the external enemy. All our heart is with YOU and our dear army. We wish it and its Leader complete success for the good fortune of our precious fatherland.’

The theme of these and other messages was not peace but victory. The Grand Duke was well known for his fervent anti-German sentiment. As a regular French visitor to Stavka, Commandant Jacques Langlois, put it ‘Everyone knew perfectly well the Grand Duke’s feelings toward Germany … The Grand Duke truly incarnated the Russian idea, the Orthodox idea, the loyalist idea, raised against Germanophile ideas.’ Compared with the ‘inner Germans’ (such as the Empress Alexandra) who had supposedly been betraying Russia’s war effort, he was seen as somebody determined to bring the war to a successful conclusion. This was the source of his popularity.

On 20 March 1917, the Grand Duke left Tiflis by train to travel to Stavka to take up command. The Belgian military attaché, General Louis-Désiré-Hubert, Baron de Ryckel, wrote to his government that the train journey turned into a ‘triumphal procession’. Eye-witnesses confirmed this. For instance, the Grand Duke’s nephew, Prince Roman Petrovich, who accompanied him, wrote that whenever the train stopped ‘crowds stood in the stations and cheered uncle Nikolasha as he stood at the train window.’ At Izium in eastern Ukraine, the train ‘was surrounded by a huge crowd. There were shouts of hurrah, people waved the national flag, and wanted to see the Supreme Commander. My uncle was forced to get out. With a loud voice he answered the greetings and declared that he was convinced of a glorious end to the war.’

In Kharkov, wrote the Prince, ‘A crowd poured in front of my uncle’s car and wanted to see him. When he appeared at the window, he was received with thunderous applause.’ According to another account, members of the local soviet of workers’ and soldiers’ deputies met the Grand Duke with bread and salt and tried to persuade him to head straight to the front to take command of the front in person and thereby circumvent any attempt by the Provisional Government to remove him. The Grand Duke refused.

Among the crowd at Kharkov station was the former Governor of Moscow, Felix Iusupov Senior. He wrote:

The masses jumped over the barriers and gave the Grand Duke a grandiose ovation. I had not seen such a powerful demonstration for a long time. The ‘hurrahs’ thundered in the air. The mood of the people was exalted and their faces radiated with some kind of brave hope and joy. They seemed to be saying, ‘Go, go, my dear, to save Russia from shame!’ How many hands lifted and made the sign of the cross on the carriage where the Commander in Chief calmly stood and bowed.

When the Grand Duke reached Stavka in the town of Mogilev, however, he found a letter waiting for him from the Provisional Government dismissing him from his post. General Hanbury Williams recorded that when word of the letter leaked out, the local railway workers came to protest and threatened to go on strike to force the government to change its mind. Nikolai Nikolaevich himself confirmed the story, writing that the workers’ representatives came to see him:

Their visit lasted for quite a long time … The workers were enraged by [the head of the Provisional Government] Prince Lvov’s letter and told me not to give up the Supreme Command. They said that they wanted to stop the trains and drum up immediately all the workers in Mogilev to send a strong message. They said that they would immediately send a telegram to Petrograd. To avoid senseless bloodshed and to avoid worsening the prevailing chaos, I persuaded them to leave it alone.

A short while later, the Grand Duke resigned his post and left Stavka for what he hoped would be an honorable retirement.The episode reveals a crucial point about the February revolution. Russians certainly didn’t like the war. Most of them would probably have been hard pressed to say what they were fighting for. But they certainly knew what they were fighting against – Germany – and they certainly didn’t want to lose.

For many, the February revolution was an opportunity not to end the war, but to wage it more energetically, to ensure final victory. And many looked to a Romanov to lead them in this struggle. The Grand Duke’s popularity derived precisely from the fact that he was seen as determined to fight to the bitter end. This fact turns upside down the way people generally see the events of early 1917. It turns out that these events were perhaps not so much as a revolution against the Romanovs as a revolution against the Germans.

by Guest Sun Mar 12, 2017 1:26 pm

by Guest Sun Mar 12, 2017 1:26 pm

boomer crook

boomer crook

Imaš PM.

Imaš PM.