Bettel's anger highlights a bleak truth: the EU27 just wants Britain to go

Luxembourg PM’s exasperation is shared by EU officials and national leaders

Jon Henley

It was, by any standards, an unusual spectacle: the leader of the European Union’s second-smallest country deciding to empty-chair the British prime minister at what was supposed to have been a joint press conference after their meeting.

Ostensibly, logistics were the problem: No 10 was concerned by the small but very noisy protest awaiting Boris Johnson outside; Luxembourg government officials said there was no room big enough to move the event inside.

Whatever the reason, the press conference that Xavier Bettel ended up giving alone – gesturing to the lectern where his counterpart should have stood – served as a striking symbol of EU leaders’ mounting frustration with the Brexit process.

The Luxembourg prime minister did not hold back. The leave campaign had been built on lies, he said. Johnson’s oft-repeated claims of progress in the talks were baseless. London had come up with nothing to replace the backstop.

Above all, the UK – not the EU – was to blame for the impasse. “I just want to repeat and remind that Theresa May accepted the withdrawal agreement,” he said. Britain’s “homemade” problems were causing “general problems” for the whole of the EU.

This was barely concealed anger – not just at the uncertainty and stress being endured by citizens, companies and countries who, after three years, “want and deserve clarity”, but at the disingenuous game being played by the British government.

Johnson has talked, repeatedly, of “real signs of movement” in Berlin, Paris and Dublin on getting rid of the backstop, the perennial obstacle to a Brexit agreement. “A huge amount of progress is being made” in the negotiations, he insists.

For EU officials, the regular meetings with Johnson’s special envoy do not even qualify as “negotiations”. There are grave doubts, after his suspension of parliament and failure to advance any concrete proposals, that the prime minister wants a deal at all – and, should one be achieved, that he could get it through parliament.

Ideas for an all-Ireland regulatory regime for food and agriculture, which No 10 thinks would go a long way to replacing the backstop, fall far short of the requirement to protect EU markets from dangerous goods, fraud or unfair competition.

And as Bettel’s exasperation made clear, officials in Brussels, and leaders in national capitals, are running out of patience. Hopes that Britain might eventually give Brexit up as a bad job and remain in the EU are giving way to prayers that it won’t.

Many now dread the prospect, remote as it may seem, of a second referendum. “Why on earth would you want a country so bitterly and hopelessly divided to stay?” asked one diplomat. “The wounds are going to last generations. How damaging would that be to Europe? Come back, maybe – but leave and sort things out first.”

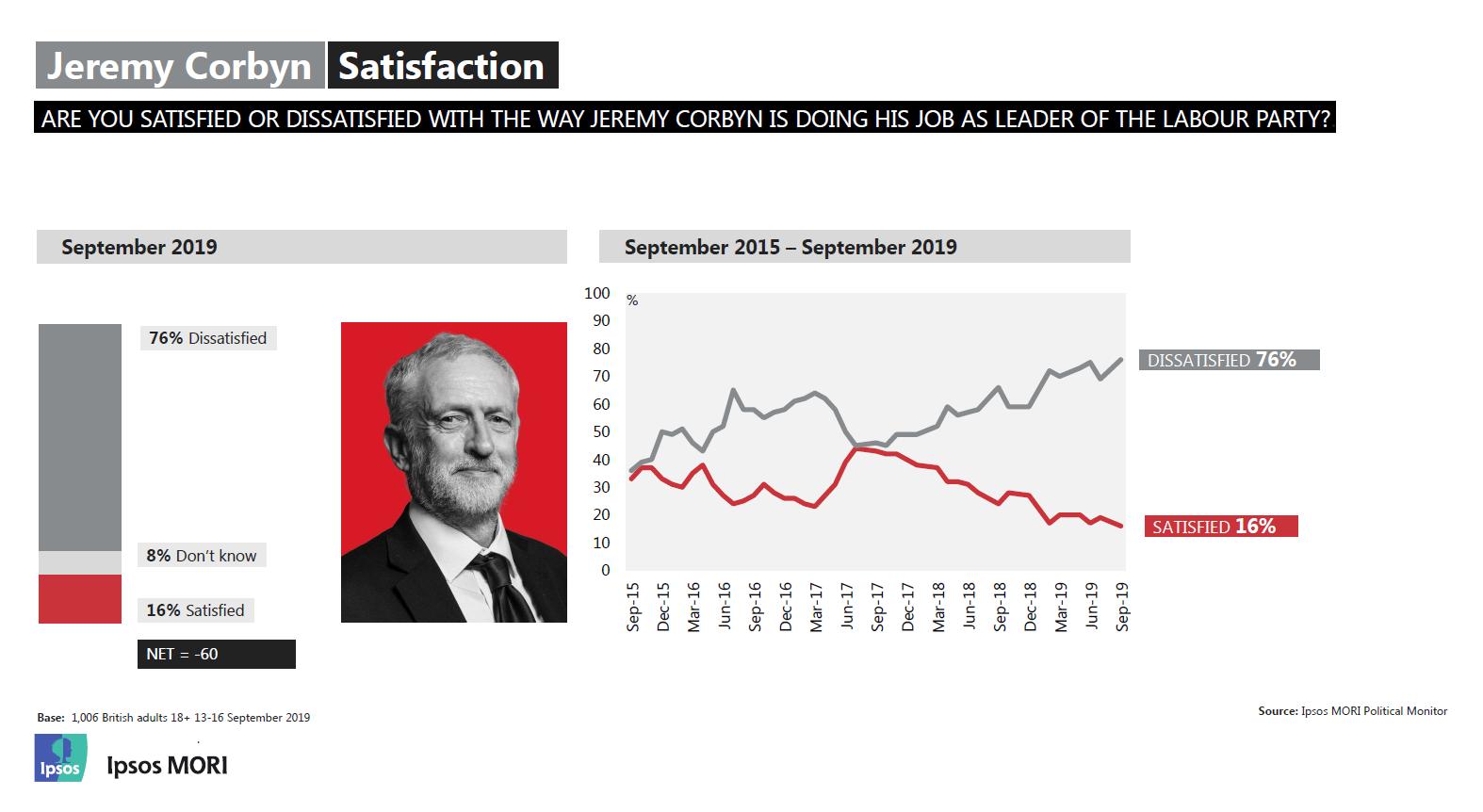

The EU27 members do not trust Johnson, but many have little confidence in Jeremy Corbyn or in the quarrelsome tribes of remainers either. Certainly, they would rather have a deal: no one wants the chaos and economic pain of no deal, or to be seen to be giving Britain a helping hand over the cliff.

But that deal clearly cannot come at any cost. Twenty-six member states will, first, never abandon Ireland when it insists on the need for an operable backstop because, despite the clout of Germany and France, the EU remains a club of small countries, most with populations smaller than 10 million.

Equally important, the European priority remains – as it has since June 2016 – the integrity of the EU single market. EU businesses are lobbying their governments, but not in order to persuade them to offer the UK a favourable deal so that sales of BMW cars and prosecco are not hit too hard.

No, European businesses want their governments to avoid any risk of British companies retaining privileged access to the single market while undercutting them by disobeying its rules: a weakened single market is a far more damaging prospect than even a no-deal Brexit.

For all those reasons, the EU would, on the whole, prefer Britain to leave now, if possible quite soon. And as Bettel’s irritation showed, it is fast tiring of a psychodrama that is costing it time, money and anxiety, and that is none of its making.

by Anduril Wed Sep 11, 2019 10:44 pm

by Anduril Wed Sep 11, 2019 10:44 pm